Ade Adepitan on his wheelchair basketball career and becoming a television presenter and author

Ade Adepitan MBE is a wheelchair basketball Paralympian, TV presenter, travel journalist and children’s author. His career spans over 20 years including winning four medals in the Paralympics and more recently presenting big sporting events, such as The Invictus Games, The Rio Paralympics and The IPC Athletics. He is also a well-known face of the BBC, having presented documentaries such as World’s Busiest Cities and What Britain Buys and Sells in a Day.

Our writer, Emma Purcell, had the pleasure of interviewing Ade Adepitan about his life with a disability and his extraordinary career in sport, television and children’s literature.

Ade Adepitan was born in Nigeria where he contracted polio as a baby, leaving his left leg completely paralysed. At aged 3, he and his family moved to the UK – somewhere that could provide him with a better upbringing for his disability.

At aged 12, Ade was introduced to wheelchair basketball and went on to compete for Team GB at Paralympic, European and World championship levels. In 2005, Ade was awarded an MBE for services in sport.

Ade started out his presenting career fronting children’s programmes, such as Tiger Tiger, X-Change and Desperado’s. He then became a reporter for documentaries including, The Travel Show (BBC) and Unreported World (Channel 4).

These days he is a well-known travel journalist and last year fronted his own BBC2 show Africa with Ade Adepitan.

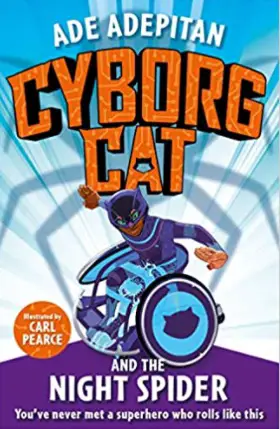

Ade Adepitan has also written a trilogy of children’s books called Cyborg Cat, which includes themes around diversity, equality and friendship.

In 2018, Ade married singer/songwriter Elle Exxe. The couple has recently launched a YouTube channel together called Adepifam.

Read on to find out more about Ade Adepitan in his own words.

Ade Adepitan living with his disability

What was it like growing up with your disability?

It was difficult, in part because my disability is a combination of things. The fact that I went to a mainstream school in the 70s, where I was the first and only kid with a disability, and one of the few black kids, made me feel very different straight away.

There were definitely some positives though because of being good at sport. It earned me a lot of respect amongst the other sporty kids, who would never have expected to see someone like me with a physical disability playing sport.

I walked with calipers, so people could see that I looked disabled straight away. In their mind, it was counterintuitive that someone like me would be good at sport.

But I had good natural hand-eye coordination. I was also a good communicator, which got me a lot of friends and a lot of respect, especially in the early days.

How does your disability affect you on a daily basis?

I’ve always been really independent and not let my disability hold me back. I left home at aged 17.

Don’t get me wrong, there have been things that can affect my disability. But I’d say that disability is a societal thing. It is a society that makes you feel like you have a disability, not your actual physical disability.

For instance, if the public transport system is inaccessible, then you feel that you’ve been impacted, and you can’t do as much as you want to. Or if buildings aren’t accessible, you feel more disabled too.

It is also about people’s mindsets about how they act around you, which can affect your perception of yourself and make you feel more disabled.

Ade Adepitan becoming a wheelchair basketball player

How did you first get into wheelchair basketball?

I was spotted by physiotherapists Owen McGhee and Kay Owen, who worked at a school for disabled children based in East London, near to where I lived.

They were very much ahead of their time in the 80s. They felt that disabled children were not being prepared for life in the real world. So, they set up a sports club. It was an opportunity for disabled kids to play sport at a club level. This included a basketball team.

Owen and Kay had heard about me because I’d done a sponsored walk for my school and was in the newspaper. They wanted to get in contact with me to see if I would want to play for their basketball team.

At the time, I’d never heard of wheelchair basketball before. It didn’t have the same sort of disability sport profile that it has today.

Back then, nobody ever spoke about any disability sports. If you were disabled, it was really difficult for you to find out or even come across disabled sports.

So, when they asked me, I looked at them as if they were mad – I couldn’t work out how it would be possible to do it in a wheelchair. There were also a lot of stigmas and negative perceptions around disability and using a wheelchair.

As a 12 years old kid, I just wanted to fit in at school. I was a little bit ashamed of being disabled. So, the idea of getting in a wheelchair was just horrifying.

Thankfully, these physios convinced me to go to Stoke Mandeville, where they were hosting the Junior Wheelchair Games.

What was it like playing wheelchair basketball for the first time?

When I got there, I was slightly overwhelmed by how many other people there were with disabilities. Having gone to a mainstream school, I wasn’t used to seeing that many disabled people.

Suddenly, was amongst people with spinal cord injuries, cerebral palsy and similar disabilities to mine. But they were nothing like how I thought they would be.

They were all really active and confident. It was really amazing. It was like a breath of fresh air.

I also saw some of the members of the men’s Great Britain basketball team, who were training there. These guys were incredible. They were like titans on the court, just flying around at speed.

I also thought they would have horrible looking wheelchairs, but they were so smart, colourful and super athletic.

I remember watching an amazing moment where one guy with a double amputation crashed into another guy and went flying out of his wheelchair and tumbling across the floor. He literally just got back into his wheelchair, high-fived the guy who knocked him out and then carried on playing.

That was the moment when I thought, “I want to play elite sport and be a wheelchair basketball player.”

You were offered an opportunity to study and play basketball at the University of Illinois in Chicago. Why didn’t you go?

I was offered a scholarship, but because I was a foreign student and their program was in its early stages, only half of the fees would be paid.

If you know anything about American colleges, you’ll know they’re super expensive. I think at the time they needed me to pay $19,000 and at 18 years old, I didn’t have that kind of money.

I tried to raise it, but I couldn’t get anywhere near that amount. It was a missed opportunity. I felt really sad because I really wanted to go and who knows where it might have taken me at the time.

Fortunately, things did turn out alright in the end. At the same time, I was also offered a professional contract to play wheelchair basketball in Spain.

At the age of 20, I took the step of moving from East London to Spain and played wheelchair basketball with CAI CDM Zaragoza for two years. It was fantastic.

I learnt to speak Spanish, played professional basketball and travelled all around Spain. It was an incredible period of my life.

What was your highlight during your wheelchair basketball career?

I would say making it into the Paralympic squad, as well as winning medals in Athens – both were fantastic. I’m also very proud of winning the World Championships.

It was all made so much more worthwhile because of how hard I worked to get there – it took me the best part of 15 years to make the Team GB squad.

This is because I was cut from the team about seven times. On numerous occasions, over a period of 10 years, I was told that I wasn’t good enough.

So, when I was finally selected for my first Paralympics in Sydney in 2000, it felt like an incredible achievement. This was the moment that got everything started for me.

Without getting a place on the team, my career wouldn’t be what it is today.

Ade Adepitan as a television presenter

How did you first get into TV presenting?

I think it was just another lucky moment for me. There was a cable TV channel called Channel One. A producer there was tasked with making a series about extreme sports, and one of the sports he chose was wheelchair basketball.

He wanted to spend some time with a wheelchair basketball player who played for Great Britain. He contacted a friend of mine, who then asked me if I’d be up for it.

I said I’d love to, but at the time I didn’t play for Great Britain. However, my mate said that no one in the able-bodied world has a clue about disability sports, so I could say I play for Great Britain and nobody would know any different!

I was worried that if they found out the truth, I’d look stupid. But they were offering £250 for a day’s filming and I was broke at the time. So, I said, “Wow £250 – tell him I’m the captain of the Great Britain team.”

The producer came along to the filming and we spent the day together. He really enjoyed my company and said that I came across really well on camera. He gave me his number and said we should stay in contact.

When I told him I’d be in Spain for a couple of years, he gave me a camera and said, “When you go to Spain, film everything. When you come back at Christmas, give us the footage and we’ll edit it and turn it into a video diary.”

They named the production after a well-known documentary called Hoop Dreams, and it did very well on Channel One.

When I came back from Spain, the guy started his own production company called Two Hands Productions, and they were looking for presenters for a children’s programme on Channel 5.

I didn’t think I had any chance of making it, but he pushed me to audition. I think he impressed on the head of Channel 5 that it was really important to have someone like me presenting it, so I got it. They believed in me more than I believed in myself.

Next thing I knew I was travelling around the world presenting a children’s show called Tiger Tiger about adventure and animals.

How did your career in TV progress from that first show?

Off the back of my work on Tiger Tiger, I was introduced to Dermot O’Leary, who was an up and coming presenter at the time working for T4. He gave me his agent’s number, but I threw in the bin because I was too embarrassed to call.

Luckily, the agent called me after a few months because he’d seen me on TV. Having met with me, he thought I had a lot of potential, so wanted to help me with my TV career.

It was difficult at first. We had to work really hard to convince a lot of TV heads to give me the opportunity because there was still a lot of prejudice and negative perceptions about disability.

There was uncertainty around whether I would be able to present and whether people would watch me.

It took me between 10 to 15 years to get to where I am today. I started in 1999 and I think my career has only really taken off in the last two or three years.

What have been your favourite programmes to present so far?

I enjoyed being involved in a CBBC fictional drama called Desperado’s, where I played one of the main characters. I also helped with writing and generating ideas. It was a 10-part series about a wheelchair basketball team and I played the head coach.

I was really proud of when I went into documentary making on the Channel 4 programme Unreported World.

And I’m very fond of The Travel Show. It’s my bread and butter, and I’ve been doing it since 2014. It’s taken me all over the world, is incredibly fun and means I get to work with fantastic people.

Of course, the Paralympic Games coverage, in which I was hosting the main show alongside Clare Balding, was incredible.

But I suppose the highlight of my career, apart from the Paralympics, is my documentary series called Africa with Ade Adepitan on BBC Two.

It was the first series about Africa on the BBC in almost 10 years and the first four-part series presented by a black disabled presenter for the BBC. It even had my name in the title – you can’t get much bigger than that.

You regularly present the BBC’s The Travel Show. What has been your favourite place to travel and why?

Everyone asks me about my favourite place, and it changes day-by-day. I’m just really lucky that I’ve been able to travel to almost 90 countries so far in my lifetime.

In terms of beauty, my favourite place is the Maldives – it is pretty amazing. Bermuda is absolutely stunning as well, especially as I was there for the carnival, which was great. I also loved seeing the Victoria Falls in Africa.

What I also love about The Travel Show is that it definitely proves that disabled people can travel and it’s opening up more opportunities. I hope that what I do inspires other disabled people to go out and travel.

It’s also watched by nearly 90 million viewers worldwide, so it will hopefully change perceptions too, both within the countries that I visit, and the travel industry. Travel should be marketed towards people with disabilities as much as everyone else.

Have you got any future TV projects in the pipeline or programmes due to air soon?

Just before lockdown, I was halfway through making a BBC documentary series about climate change. So far, I’d been to Australia, the Solomon Islands, Bhutan and Bangladesh. We had China and the USA left to go.

It’s a three-part series and we’ve put so much work into it already. Climate change is also a really, really important subject that we need to talk about, educate people on and properly tackle.

Fingers crossed, we’re hoping to resume filming sometime in September and have the programme air later this year or early next year. It was going to be my second big series.

Can you tell us about your new YouTube channel Adepifam?

My YouTube channel called Adepifam, which I’m doing with my wife Linda, launched at the end of August. It documents our lives and enables people to see behind the scenes of making TV programmes.

My wife is a singer/songwriter and musician, so you’ll also get to see her when she’s making music, writing songs, building her studio and going to gigs.

We also talk about relationships and what it’s like to be in an inter-abled and an inter-racial relationship.

We touch on what it’s like to find love when you have a disability, and look at things from Linda’s point of view as an able-bodied person, including what her perceptions of disability were before meeting me.

We’re tackling those difficult topics that no one talks about, such as disabled people having sex and becoming parents. We aim to upload new episodes every Friday at 9pm.

Ade Adepitan as a children’s author

You’ve written a collection of children’s books. What inspired you to become a children’s author and how did you come up with your story ideas?

I was initially going to write an autobiography because a lot of my friends said I should do it and talk about all my life achievements.

I decided to write a chapter and send it out to a few publishers. Piccadilly Press came back and said they felt that my story could translate really well into a children’s book, due to the fact there was a lack of diversity amongst children’s authors.

Most children’s authors are white, middle-class people. There aren’t many disabled writers or authors from different ethnic backgrounds, or even from working-class backgrounds. We also really wanted to try and get more boys reading.

I wrote a couple of chapters, with the idea of basing them loosely on my life story, as well as creating a story around a disabled superhero.

What is your book series, Cyborg Cat, about?

It’s about a young kid called Ade who is a disabled superhero. He moves from Nigeria to the UK and is trying to fit in at school. He uses a calliper to help him walk after having contracted polio – similar to me but without the superpowers.

He makes friends with a group of kids who aren’t seen as ‘cool’ and are all different for certain reasons.

There is Brian, who’s the nerdy and super intelligent child; Shed, who is a big gentle giant kid from Pakistan; Melody, who’s a mixed-race girl and talented footballer, and Dexter who comes from a working-class, white family.

Throughout the stories, the kids come together and go on adventures, solve mysteries, take on the school bully and just have lots of fun.

The books are about friendship, showing that it’s okay and cool to be different, and that each and every one of us, no matter where we come from or what we look like, we have the ability to be superheroes if we believe in ourselves.

Have you got any books scheduled for release later this year or next year?

I’ve signed a three-book deal. The idea was to continue with that and write more books. But, unfortunately, some of the publishers are furloughed. We’re currently waiting for everything to be sorted out and negotiations to happen.

I really want to continue writing and I think they want me to do maybe another two or three more books in the Cyborg Cat series.

Ade Adepitan’s charity work

You support numerous charities. Is there one that you’re most proud of or that is closest to your heart?

I’m proud of all the charities I’ve worked with because I try to work with ones that I feel I have a connection with.

The one that’s closest to my heart is Go Kids Go (previously the Association of Wheelchair Children), which teaches disabled children and their families wheelchair skills and how to become independent.

The charity does such an important job. People forget that when a kid is given a wheelchair, they won’t automatically know how to use it, how to do wheelies or how to get up or down steps.

To have a charity like this that teaches those skills gives parents peace of mind that when their kid go to school, they’ll be fine because they know how to use a wheelchair and have confidence using it.

Go Kids Go also ran the wheelchair basketball club that got me into disability sport and started my journey off. I’m super proud of my connection with the charity and I’ll always be associated with it.

What advice would you give to disabled people wanting a career in sport and/or television?

Go for it! Don’t let anything hold you back if it’s your passion. I never really got into television or sport to become famous. I got into these things because I love and enjoy them.

As a basketball player, I was prepared to get up very early in the mornings. While my friends were out partying or on holidays, I was on the basketball court training and that was because I loved the sport

The same with TV – when we travel around the world, it’s not always glamorous; travelling in economy class, horrible hotels sometimes, getting up early in the morning and travelling long distances. You also have to learn lots of stuff and be on the ball all the time.

So, you have to be prepared to do the stuff behind the scenes that no one sees. If that’s what you really want, then I’d say, just try it.

We need more diverse people on TV, and we need more opportunities for young people, especially disabled people playing sport.

Recent Achievements 2024:

Since 2020, Ade Adepitan has continued to excel in his broadcasting career and advocacy work. Notably, he presented a new documentary for Channel 4 titled Whites Only: Ade’s Extremist Adventure, which premiered on 18 March 2024, where he explored the whites-only town of Orania in South Africa

Additionally, he has been involved in various other projects, including presenting the BBC’s Children in Need appeal and participating in TV shows such as Catchphrase and Blankety Blank

To find out more about Ade Adepitan, you can follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Interview by Emma Purcell – follow her blog Rock For Disability

Main image by Ian Wallman

More on Disability Horizons…

- Influential voices in the disability community reflect on Life After Lockdown

- Cerrie Burnell: disabled actress, author and TV presenter

- 8 influential black disabled men to follow

- Ade Adepitan MBE to be made a patron of learning disability theatre group Blue Sky Actors