Using poetry and writing to overcome disability

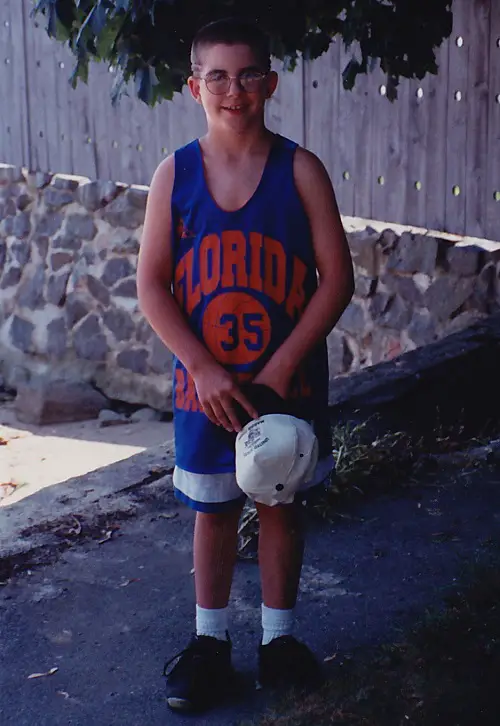

American poet and writer Christopher Reardon dreamt of playing sport from a young age. But a brain tumor in childhood, which left him partially paralysed, meant he had to refocus his goals. What was his savior? Writing and poetry.

When I was younger, my whole life was about practising and craving to play football as soon as I was eligible. But I was a husky kid. You wouldn’t be wrong if you said that’s just a nice way of saying ‘fat’. Tall. I was that, too. My weight was always an issue because it oscillated back-and-forth from the weight amount that was league-mandated. That wasn’t the only problem I had when it came to playing football.

The fall of the year I could have started to play football, at the age of eight, a doctor at Boston’s Children’s Hospital diagnosed me with a brain tumor on my brainstem. I’d been having hundreds of mini-seizures or ‘episodes’, which is what prompted the diagnosis.

The diagnosis was crushing, but thank goodness for it. With what we know about football today, and the way I used to use my head and fling my body around during the game, football could have been a very dangerous thing for an eight-year-old me.

So, I had brain surgery to remove the tumor, but it was unsuccessful because the tumor was wrapped in nerves. I was supposed to be in the hospital recovering over Christmas, but I was out in a week.

I went on living life like a normal kid. After tears in the doctor’s office when he told me I couldn’t play football, I started playing basketball, which I probably would have done, anyways as my father and sister already did. To this day, consider myself a ‘hoop head’.

Treatment for the brain tumor

Two years later, the tumor started moving again, and it was decided that I would have proton radiation therapy. At the time, proton radiation was brand new, and there were only two machines in the world that could do it (there are now 40), one very close to where I lived.

The treatment involved my arms being strapped to a wooden chair and a white, plastic mesh mask put over my head. It sounds like something out of a horror film, but at the time, I thought it was fun – I was just 10.

Late that summer, while playing a summer league basketball game, I missed a court-length pass, even though I was all by myself under the basket. Right then I knew that the swelling the doctor said would happen was indeed happening.

My declining health

Things started going downhill fast. The left side of my body became ataxic, meaning I lost co-ordination in my muscles. My left vocal cord became paralysed, so I could only eat soft foods. I was getting physical and occupational therapy weekly, as well as MRIs and breathing treatments to bolster my immune system. After struggling with a walker for a few months, it came as a relief when my wheelchair was delivered in April.

I had another brain surgery to ease pressure from my swelling, but the surgery didn’t do much. I gained forty pounds of water weight from high dosages of steroids, had a puffy face and erratic sleeping hours.

That period of time was literally a blur – I was legally blind for several months until my sight came back suddenly. Just in time to do my summer reading for school.

Discovering poetry

I will always have a fondness for my seventh-grade teacher who assigned us a task to write a poetry book. Without knowing it at the time, she gave my life a new focus.

Before that, I had written only one poem in my life. A surprisingly morbid, perhaps fortuitous, poem that spelt out my anarchic ethos:

Why, oh, why,

Oh, we did we try,

You and I,

Oh, why?

But that was in the third grade before I knew of existential philosophy or the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas who wrote:

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

This is my motto.

For the most part, I didn’t like the assignment, but my last poem, which could have been about any topic in any style, was about my disability. Then, right at that moment, while writing my sixteen-line poem, that thing called passion kicked in.

Writing about disability

Once getting to high school, I wrote poetry constantly. Mostly angsty, juvenile stuff, but I like to think of it as ‘honing my craft’. My poetry reflected someone in a wheelchair trying to navigate the social minefield that is high school, which, for anyone disabled, is a hundred times trickier.

At the end of senior year, I got aspiration pneumonia and was in the intensive care unit for seventeen days. I mention this because this near-death experience meant so much more this time around because I was mature enough to comprehend what was going on around me.

I was also informed that I had double paralysis of the diaphragm, something called Ondine’s Curse, and got a scratched cornea when a bi-pap mask leaked air into my open eye while I was in an induced coma. But I carried on and pushed forward to enrol in the University of Arizona.

I loved everything about the university. I really did. But, at the time, I was introverted and struggling with my disability. So I transferred to a much smaller university college in Massachusetts, nearer to my family.

To my delight, the English faculty was nothing short of brilliant, and I formed a close bond with several members. This is where I really developed as a writer. I wrote my first book, a self-published memoir, as well as the fictional stories I later used in my graduate thesis.

Becoming a published writer

I started writing prose – a slightly less formal style of writing to poetry – because I thought I might I have a chance at making some money, but guess what? That hasn’t panned out. I don’t know why people don’t read poems in our short-attention-span-culture, even though they’re brief and can be done with quickly.

I think it’s because people are still afraid of poems, like they’re too complicated or can’t be understood. But I have found that the great poets write poems that can be enjoyed by all. An individual’s interpretation of a poem is not a matter of depth, but rather a three-dimensional endeavour. I distil the language of a poem and make it precise as possible so that it seems to me like a dynamic idea or object that I could find in the world of a novel.

After college, I earned a master’s degree in writing and furthered my development as a writer with the help of some talented professors who gave me a more global approach to literature, which I thoroughly enjoyed. I self-published my second book, a book of novellas and poems. But, like many writers, found myself unemployed with my graduate school buddy. We would spend our days watching movies and then debating them.

To diversify, I started writing screenplays too. In 2015, my second screenplay Lagom (the Swedish word for ‘just the right amount’) was a finalist at the Catalina Film Festival. I almost filmed my first screenplay (a full feature-length), but on the day before filming, the camera crew substantially increased their price. So, I have stuck with writing, self-publishing two more books of poems, and continuing to work on my novel and collection of short stories.

If you’re interested in writing…

A great writer told me that: “Literary journals are the gatekeepers” and they are. So my advice to any disabled writer is to first try to get published in disability literary journals like Kaleidoscope, Breath & Shadow, www.wordgathering.com, The Deaf Poets Society, Bellavue, Tiny Tim Literary Review, Intimaor and The Examined Life, as well as Disability Horizons, New Mobility Magazine, Rolling Inspiration and Autonomous Press. Build a resumé while finding your uniquely disabled voice.

I’m afraid to say it aloud because I worry about people’s reactions, but I am lucky. How could I be lucky? With my medical history and such? Do people think me a fool for considering myself lucky? Then I think about being born in the geographical location with the best hospitals in the world, about being born in a time when advancements like proton radiation and immunotherapy are made, about being born in a socially progressive era, about finding a passion like writing and film—luck is a random slash by the dual blade of a sword.

Then I think about being born in the geographical location with the best hospitals in the world, about being born in a time when advancements like proton radiation and immunotherapy are made, about being born in a socially progressive era, about finding a passion. Luck is a random slash by the dual blade of a sword.

By Christopher Reardon

Get in touch by messaging us on Facebook, tweeting us @DHorizons, emailing us at editor@disabilityhorizons.com or leaving your comments below.

https://disabilityhorizonscom.onyx-sites.io/2013/02/the-benefits-and-perils-of-working-as-a-disabled-freelance-writer/

https://disabilityhorizonscom.onyx-sites.io/2017/05/me-and-me-making-films-about-disability-to-raise-awareness/