Changing perceptions: don’t think of me as disabled

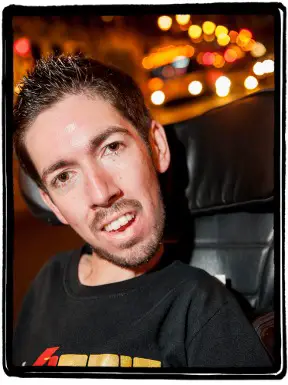

My name is Jimmy Curran. Looking at my picture, the first thing you probably notice (after my good looks) is that I’m in a wheelchair, or that I’m ‘disabled.’ But what exactly does that mean? By definition, disable means; “to deprive of capability or effectiveness.” But if you got to know me, I don’t think you would characterise me that way.

I went to college at Temple University, graduated with honors, did internships in New York and Washington, and now work full-time for a major health insurance company in downtown Philadelphia. I also recently published a children’s book titled Will the One Winged Eagle, which I wrote and was illustrated by Kris Napper, a graphic designer who also has SMA.

But more importantly than all of that, I live independently with assistance from aides in my own apartment, surround myself with my amazing family and friends, and live each and every day like I won’t get another one. So tell me, how disabled am I?

The term disabled alone breeds the negative misconception that those with disabilities cannot. But my dad taught me can’t means won’t, so I do. I can’t walk, but you probably can’t dunk a basketball on a 10-foot net.

My point – our limitations don’t define us. Everyone has limitations – and everyone has the ABILITY to use their strengths and resources to circumvent those limitations. Life is too short to make excuses. Disable your limits.

Eddie Doyle

I met Jimmy at university, and over the next decade of friendship, I experienced so many crazy, hilarious, wild and perspective-shifting moments with him. What really struck me, though, is how so many people seemed interested in Jimmy, and how their perception of him was so far off from the reality I had come to learn.

So I wrote down some of our best stories in the recently published memoir I hate you Jimmy. The following are a couple of excerpts from the book.

I hate you Jimmy extracts

Meeting Jimmy

For me, it was his hands. It’s not that I couldn’t stop looking at them… it was all I wanted to look at. It was the visual I let my eyes hang on as I acted like I was looking around, like a perfectly filled bikini top, or your best friend’s cold sore. It was what I fixated on when he was looking away and I knew he wouldn’t catch me. It was what struck me as most abnormal, disfigured, different.

Maybe it was because they were crippled, bent at the wrist, barely moveable. Long, skinny fingers that looked like sharpened-down pencils with a matching thumb tucked underneath.

Maybe it was because he was able to use that deformed body part for so many things – handling his chair’s joystick, using his phone, and, to my surprise, to sign his name or feed himself if necessary.

Maybe, actually, most likely, his hands stood out to me because I had been teased for my own short, stubby fingers and I focused on his as a result of my own insecurity.

Regardless of the reason, it was his hands that stuck out to me. For you, maybe Jimmy stands – err, sits – out when he’s throwing back shots at the party, and suddenly you find an exception to the rule about never drinking and operating a motor vehicle.

Maybe it is seeing the wheelchair at the after-hours bar, or the five-star restaurant, or the professional sporting event. The seemingly hopeless and heartbroken expectation of disability being met with crisp Gucci shoes, a button-down Burberry shirt, the scent of sophistication, and a scarf meticulously wrapped around his neck, the logo positioned to make sure the world sees the little guy on the horse.

Maybe the disconnect comes when you see this handsome young man courtside at an NBA game chatting it up with the players, or smooching with the Sports Illustrated swimsuit model in the middle of the bar, settling for a prolonged kiss only because his condition does not give him the strength needed for a frencher.

Even more interesting than the way Jimmy interacts with the world is the way the world interacts with him. The waitress who asks me what Jimmy is going to have, even as he is sitting there reading the menu.

Or the impatient bathroom line, making rude comments and banging on the door, until it swings open and everyone quietly adjusts their attitude as they clear a path for the wheelchair.

The girl who is left speechless when this cute, innocent little man she spent the evening talking to invites her back to his apartment as the bar is closing.

Or the visible shift from an expression of anger to apology after a guy’s been nailed in the back of the leg with an unknown object and turns around to find he’s been struck by muscular dystrophy.

Jimmy has a special power to hit someone – and hit them hard – and have the victim say “sorry.” For what they are apologising, I still don’t know.

Most revealing, however, is the uncontaminated reaction from children. It’s not uncommon for a child walking past Jimmy to continue moving forward while his head turns and turns and turns like an owl, perplexed and cemented on this person who is similar in size but looks so dissimilar to themselves.

It is a raw look of confusion, a look that says; “you are different than me.” Usually this is followed by a guilt-ridden, hushed scolding from a nearby parent who’s telling the kid not to stare. I don’t know if the child gets scared of how Jimmy looks, or upset that this happened to someone, or bewildered as to why it would happen. What I do know is that it is a pure reaction, one not masked or inhibited by years of trying to make sense of the world.

And, no matter whether you are young or old, seeing, meeting, or interacting with Jimmy threatens to change the bubble of the world you have created for yourself.

Bathroom beers

Another Friday night, and another trip to the bar, and another call from nature had me following Jimmy to the bathroom. There was a long line that didn’t faze either of us. Not only does Jimmy rarely wait in line anyway, but it was the basement bar across the street from our place where we had become well-known. And by we, I mean Jimmy.

In fact, after a few months of Jimmy bringing our entire group in through the back, accessible entrance, allowing us all to skip the wait and cover charge to get in, the bouncer started implementing a ‘new rule from management.’

People using the accessible entrance could only bring two people in with them. We got a kick out of it because we knew that Jimmy was the sole reason for the creation of this rule, and we also knew that he was the sole person that it was implemented on. We would affectionately refer to this as The Jimmy Rule.

So I followed Jimmy as he bypassed the bathroom line and parked inside the bathroom doorway. The stall isn’t big enough for Jimmy to pull his chair into, so he’s forced to drop his pants around everyone else in the bathroom, and be carried to the toilet. To be honest, I’ve always had the suspicion he prefers that, anyway. He wants everyone to know who the big dick in town is.

I did my part, which was oddly becoming like second nature to me. With his chair slightly reclined, I unbuckled his seatbelt, crossed his arms on his chest, and lifted him by the knees so I could pull down his pants. With one hand behind his head and one hand under his knees, I picked him up, and holding him horizontally, carried him into the stall.

Angling his body so the monster hanging out was aimed to hit water, I told him to fire away. Jimmy was mid-pee when the stall door swung open. In burst some guy that neither of us had ever met before. He was holding two beers.

“Hey, I wanted to get these beers for you guys. You both are awesome. Seriously, awesome.”

Me and Jimmy looked at each other and tried to keep from laughing. As serious and appreciative as I could be, I told the stranger: “Thank you very much, that is super nice of you. I can’t really grab them from you right now,” nodding to the 63-pound man, half-naked and peeing, who I had in my arms; “and he can’t really grab them either, so if you want to set them down on the sink we will grab them in a second.”

The guy backed out of the stall. Jimmy and I tried our best to hold in our laughter because cracking up while holding someone over a toilet pissing, who is also cracking up, could be quite a mess.

Moments later, this guy walked right back into our stall, as if it was just another place in the bar. With Jimmy still peeing (Jimmy has an absurdly trained bladder. He literally went from 1st through 12th grade having never peed at school). The stranger proceeded to tell us that his brother was in a ski accident and is now a paraplegic, and seeing Jimmy and I hanging out at the bar gave him hope for his relationship with his brother.

He went on to talk for a little longer, and was even tearing up a little before he finally left. I couldn’t determine if it was a happy cry, or a sad cry – it was probably a little bit of both. But I did know that whatever it was, it was a genuine and kind emotion this total stranger was trying to share with us.

Usually, after the typical run-ins with strangers, either Jimmy or I will make some wisecrack or expletive comment. But this time, as I put Jimmy back down in the chair, we were silent. Not a word was spoken between us as we exited the bathroom, me now holding two beers. Before we got back to our crew, I tapped the glasses together in an unspoken toast, and gave Jimmy a swig before I took one myself.

Every now and then there comes a sincerity that even my cynicism, or Jimmy’s experience, can’t ruin.

Writing Jimmy’s memoir

The most interesting part of this project, for me, was that it gave me such a fresh perspective. I haven’t seen any other disability-related book from the perspective of an “able” bodied person, while still being funny and honest. It was a blast to help produce, and it was even more fun to live the stories as they were happening!

I really believe that this book will continue to serve my purpose of changing the perception of those with disabilities, one page at a time!

By Eddie Doyle and Jimmy Curran

For more information on Jimmy’s dis[ABLE] brand visit www.disablethebrand.com

More on Disability Horizons…