The UK’s unwritten history of disability

When it comes to the mainstream timeline of history, it seems that all too often disabled people are relegated to the margins, or even more commonly, rendered completely invisible. So to mark its 25th anniversary, Yorkshire based mobility dealership Bristol Street Versa decided to look into a sometimes ignored area of British history, charting the moments that changed the lives of disabled people living in the UK and looking at just how far we’ve come.

Whilst the situation for disabled people living in the UK today is far from perfect, you only have to take a look back 100, 50, or even as recently as 20 years ago to see how far we’ve come.

In the early years of the 1900s, people with mental or physical disabilities were branded as “feeble minded” by politicians and scientists. 50 years ago, there was no safety net or welfare system to support disabled people. And it was only 20 years ago that the UK passed laws making discrimination against disabled people illegal.

Changes in mobility and independence

Although progress has been slow at times, the opportunities and general quality of life for disabled people in 2016 are hugely different to compared to in 1816, or even 1916. Changes in mobility assistance have often been slow too, with real developments only taking place in the past 50 years. Most wheelchairs today are relatively lightweight, offering users a degree independence that might not otherwise be possible.

However, for much of history wheelchairs were not widely used, with only the privileged and rich classes being able to afford them. Even then, the most common chairs – or so called ‘invalid carriages’ – were so heavy and cumbersome that they almost always required another person to help push them along, removing the independence that today’s chairs afford.

Wider advances in mobility were similarly sluggish, and although the early efforts made by the automotive industry to accommodate disabled drivers were admirable, there was much to improve. Take the Invacar as an example, a small light blue three-wheeler produced by Bert Greaves to help increase the mobility of his disabled cousin. The Invacar proved to be a relative success, and a fleet was adopted by the then fairly new NHS.

However, the fleet wasn’t particularly well maintained, and vehicles often toppled over on corners, with some even bursting into flames. The founding of the Motability scheme in 1977 made the Invacar somewhat redundant, and the cars were finally banned from UK roads in 2003.

Another advance in mobility came in 1947, courtesy of a Canadian veteran named Walter Callow, widely recognised as the inventor of wheelchair accessible vehicles. Callow – left blind and quadriplegic following a plane crash – first used his custom made converted buses as transport for injured WW2 veterans, later receiving the support of General Motors to produce a whole fleet.

The First World War

A First World War veteran, Callow’s achievements illustrate the wider range of opportunities that began to become available after that war. In the hundreds of years prior to the First World War, the general prevailing attitude was that disabled people were a burden on society. During the Victorian era, this ‘burden’ was dealt with by the creation of the Workhouse, where those physically unable to work were separated from wider society, and effectively incarcerated.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Francis Galton – a cousin of Charles Darwin – devised further ways to deal with the ‘problem’ of disability. Galton promoted the theory of Eugenics, which sought to improve the long term ‘quality’ of the human race by effectively breeding out those with physical or mental disabilities. For much of the late 19th and early 20th century, Eugenic theories were believed by the wider scientific populace and general public, and disabled people continued to be viewed as separate to wider society.

However, the tragedy of the First World War led to a revaluation of these ideas. Veterans returned injured in larger volumes than any previous war, and disability became an increasingly common sight in towns and cities throughout the UK. Injured veterans couldn’t be viewed as having ‘faulty genetics’ any more, as was taught by eugenicists, and a small cultural shift in attitudes towards disability took place. Although disabled people were still ‘other’, the First World War was arguably the spark for much of the progress of the 20th century.

Employment and equal rights for disabled people

In the following years, through marches, protests, and campaigns, disabled people began to make themselves heard in a way that had never been done before. In 1920, the National League of the Blind organised marches on Trafalgar Square to pressure the government for equal opportunities, using the slogan “Justice Not Charity”. This slogan summed up a common goal for many of the similar disability movements, highlighting that the aim of campaigners wasn’t to achieve any special rights, but simply equal rights.

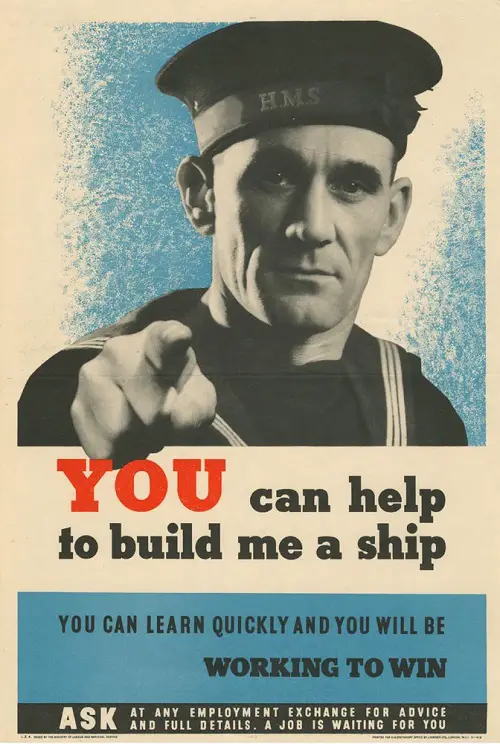

The Second World War was another key moment for civil rights. Labour shortages during the war meant that disabled people, who may previously have struggled to find work, became valued parts of the national workforce. In 1944, the Disability Employment Act placed a duty on employers to ensure that at least 3% of roles were offered to disabled people. Following the war, the government founded Remploy, which provided ‘sheltered work’ for disabled people in specially designed factories. By 1953, Remploy employed over 6,000 people in 90 factories across the UK, something unthinkable half a century earlier.

With so much progress in the early half of the century, it’s shocking to think that one of the most important steps only came in the 1990s. After years of pressure from disability campaigners, the government passed the Disability Rights Act in 1995, which made it illegal to discriminate against a person based on their disability.

The 21st century has seen much progress too, with the wide televising of recent Paralympics raising the profile of disability amongst the general public, and politicians like Jane Campbell and Anne Begg providing a voice in the Houses of Parliament and Lords.

However, it’s safe to say that much progress still needs to take place, and considering the recent events of the EU referendum, it’s difficult to predict how life in the UK might change for disabled people in the coming years. Let’s hope it means more progression, not regression.

Head over to Bristol Street Versa to view its full timeline history of disability in 25 moments.

By Bristol Street Versa

More on Disability Horizons…

- Face mask exemptions: how to ensure you don’t get fined if you’re exempt

- 80% of disabled people have experienced accessibility issues with online streaming services

- Disabled filmmaker wins award in Best Shorts Film Competition

- Find stylish and practical disability living aids on the Disability Horizons Shop

Get in touch by messaging us on Facebook, tweeting us @DHorizons, emailing us at editor@disabilityhorizons.com or leaving your comments below.