Breast Cancer Awareness Month: tips to overcome barriers to cancer screening

Disabled women don’t have the same access to screening for breast and genealogical cancers as non-disabled women, and are up to three times as likely to die of breast cancer. This Breast Cancer Awareness Month, Deputy Editor Karen Mogendorff stresses the importance of participation in cancer screening and gives tips on how to deal with barriers to cancer screening.

The mere mention of the word cancer scares the hell out of most people. But cancer need not be a life-threatening disease if it is discovered in its early stages.

Screening programs for different cancers play a pivotal role in the timely discovery of breast and gynaecological bowel cancers. But, national screening programs are not designed with disabled women (or men) in mind. They can encounter a number of barriers, including:

- communication problems with care providers;

- physical access to medical equipment;

- and transportation problems.

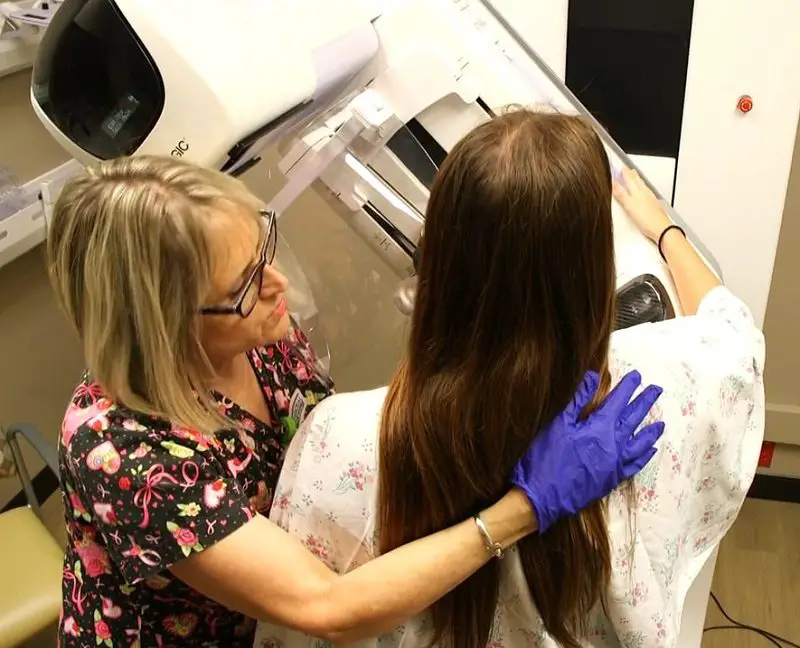

For instance, standard screening practices require you to be able to stand still for a short while, or to position yourself on the examination table. With screening for gynaecological cancers, women need to be able to spread their legs wide. But these are requirements that are problematic, if not impossible, for many disabled women.

Disabled women who are faced with these barriers to screening may think: “I’ll just skip it, I probably do not have cancer anyway.” Doctors too may use this argument when regular procedures cannot be applied to disabled women.

It is true that most people who get screened for cancer do not have the disease. But cancer does not discriminate and screening programs are largely effective. So, it is important to get screened, no matter what your circumstances are or health is. Cancer screening saves lives.

Luckily, there are alternatives to standard screening practices, although they aren’t well-documented. Here, we share some strategies that may help you to get screened without much difficulty.

1. Don’t wait for an invitation to get screened for cancer.

Not every disabled woman receives an invitation to the national cancer screening program, even if they are eligible. So, it is important to be aware of when and at what intervals screening is recommended in the UK.

Breast cancer screening is recommended for women aged 50-75 every five years.

Cervical cancer screening is recommended for women aged 25-66.

Your family doctor will be able to tell you more about it, or you can visit the Cancer Research UK website for more information on breast screening (also called mammograms), or the NHS website for more on cervical screening.

For bowel cancer screening, both for men and women, screening is for people between the age of 60 and 74. A home testing kit will be sent to you every two years, which means it is generally easier for people to access.

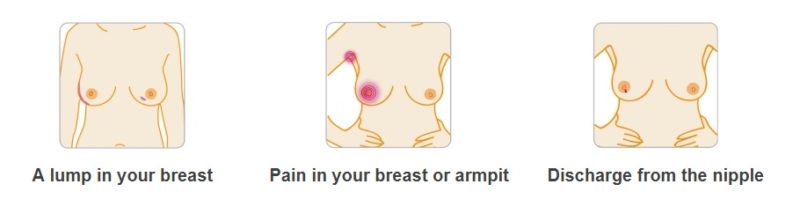

You can request a screening without invitation, especially if you fall into an age group at risk. In the case of breast cancer, it’s also good to check your breast regularly, or ask a trusted person to do it for you if you are not able to do it by yourself.

The images below will help you know what signs to look for. You can also visit the breast cancer signs and symptoms page on the Breast Cancer Awareness Month website for more details.

2. Learn about cancer screening procedures and practices.

Cancer screening is not a topic people casually talk about. But your family doctor and friends with similar disabilities may be a valuable source of information about local screening practices, including what works and does not work.

Stories about successful adaptations for cancer screening can also be found online and serve as a source of inspiration. One example is the story of Judy Panko Reis, who encountered problems with mammograms but persisted to find a solution that was right for her.

3. Actively look for a doctor who is sensitive to your needs.

Care providers sometimes insist on screenings being carried out in the normal way. This is either because they have little spare time to think about how a procedure could be adapted, or because the regular way, in their experience, has usually worked.

In addition, those who conduct mammograms or other forms of cancer screening are generally not specialised in the treatment of people with disabilities. This means that they’re rarely knowledgeable about people’s individual abilities and limitations. As such, they need to be convinced that regular procedures need to be adapted.

Doctors may be more easily persuaded when presented with solutions for accessibility problems. However, people don’t always know in advance exactly what barriers they may encounter and, therefore, how to best overcome them.

You would, therefore, benefit from the help of health professionals who are able to ‘think outside the box’ and are willing to find a way to screen that minimises pain and embarrassment. They may also provide follow-up treatment tailored to someone’s specific situation.

A good way of finding a doctor who is willing to adjust regular screening practices to your specific needs is by asking around. Disabled friends or acquaintances in your personal network or disability organisations may be able to point you in the right direction.

4. Bring someone with you for support and assistance.

Some medical staff may not necessarily be able to help you with everything you might need, such as getting onto the examination table. If you have an appointment for cancer screening, we would recommend taking someone along with you for support and practical help.

In some hospitals, there are also volunteers that can assist you, such as helping you to get to where you need to be within the hospital, or in other ways to overcome barriers to standard medical care.

5. Dare to be insistent or say no and reschedule an appointment.

Despite all preparations, appointments may still not go exactly to plan. If a care provider does not take your concerns and needs seriously and insists on doing things the regular way, don’t be afraid to speak up.

For example, in a teaching hospital, you may discover on arrival that you are to be helped by a trainee doctor, or an assistant of the doctor you originally selected for his or her disability sensitivity. They, therefore, may be not sufficiently knowledgeable or confident enough to tailor standard screening practices to individual needs.

If this is the case and you feel uncomfortable, be confident and reschedule, making sure you’ll get the right staff member and care next time.

6. The ‘show not tell’ strategy.

A way to convince a sceptical doctor that regular screening practices do not work for you is by demonstrating to them the issues you have or what does not work. This can feel like an unpleasant strategy, but it may be very effective in the long run.

For example, women with cerebral palsy may suffer from a spastic response or episode (the temporary and visible loss of control over limbs) during regular screening. Showing the doctor what happens in these situations can be a very persuasive way of conveying them that you are entitled to adapted screening, and that it would be less time-consuming in the long run.

7. Share good and bad experiences of cancer screening with others

Above all, it is good to share your experiences of cancer screening and treatment with other disabled people. Sharing will mean more people will feel supported and, ultimately, get screened with minimal discomfort. It could help to save lives.

By Karen Mogendorff

Get in touch by messaging us on Facebook, tweeting us @DHorizons, emailing us at editor@disabilityhorizons.com or leaving your comments below.

https://disabilityhorizonscom.onyx-sites.io/2017/09/accepting-your-disability-and-living-your-life/

https://disabilityhorizonscom.onyx-sites.io/2017/08/three-disabled-people-who-will-not-let-themselves-be-limited/

Originally posted on 02/10/2017 @ 12:10 am

One Comment