Asserting Your Rights: A Guide to Personal Injury Claims for Disabled People

Every year, thousands of disabled people across the UK suffer preventable injuries due to inaccessible environments, workplace negligence, and systemic failures to meet basic safety standards.

From dangerous road layouts that force wheelchair users into traffic to employers who ignore their legal duty to make reasonable adjustments, these incidents aren’t accidents—they’re the predictable result of discrimination and poor planning.

If you’ve been injured because someone failed to consider your needs or meet their legal obligations, you have rights. This guide reveals common types of personal injury affecting disabled people, the legal protections available, and the crucial steps you need to take to secure justice and compensation.

Key Takeaways

| Topic | Summary |

| Common Injury Types | Disabled people face disproportionate risks from road accidents, inaccessible workplaces, and unsafe public spaces. |

| Legal Protections | The Equality Act requires reasonable adjustments at work and in public services. Failures can lead to valid personal injury claims. |

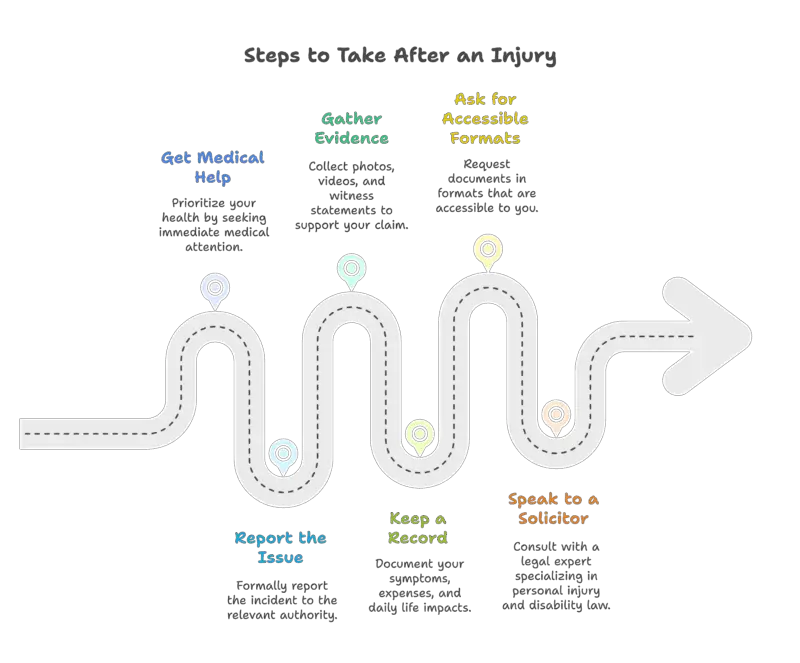

| Taking Action | Gathering evidence, reporting incidents, and speaking to a solicitor are crucial steps for protecting your rights. With the help of experts like Jones Whyte personal injury specialists, you can move forward with confidence. |

Personal injuries are often the result of environments that weren’t designed with disabled people in mind. From inaccessible streets to workplaces that ignore legal duties, these preventable barriers continue to cause harm

This guide explores the most common types of personal injury affecting disabled people in the UK, and what to do if you’ve been hurt due to negligence or inaccessibility.

Road Traffic Accidents and Disabled Pedestrians

Disabled pedestrians are at significantly higher risk on the roads. According to Road Safety GB, disabled people are five times more likely to be injured by a vehicle than non-disabled people. The reasons are often systemic:

- A lack of tactile paving or audible crossings.

- Pavements blocked by parked cars, forcing wheelchair users into traffic.

- Poor maintenance that creates hazards for mobility aids.

Although the number of motor injury claims fell by 18% in early 2025, reaching their lowest recorded level, danger remains for disabled pedestrians. Many streets still ignore basic accessibility standards. A survey by Disability Rights UK found that 84% of disabled people report serious access issues in their local area, and 97% said they’d been forced to travel onto the road due to blocked or poorly maintained pavements. If you’ve been injured because of an unsafe road layout or a driver’s negligence, UK law gives you the right to seek compensation.

Unsafe Workplaces and the Failure to Make Adjustments

Under the Equality Act 2010, employers must make reasonable adjustments for disabled staff. Yet many injuries at work stem from their failure to do so.

For example:

- Not providing ergonomic equipment, which can lead to long-term physical pain.

- Inaccessible offices or warehouses with trip hazards or blocked emergency routes.

- Lack of training among staff, resulting in unsafe or discriminatory practices.

Mental health conditions caused by an inaccessible or hostile work culture also count. Stress, anxiety, or burnout linked to disability-related discrimination can be the basis for legal action.

Slips, Falls, and Public Spaces That Aren’t Built for Everyone

A cracked pavement might just be an inconvenience to some—but for a wheelchair user, it can be dangerous. Public spaces should be safe for everyone, yet many councils and businesses fail to fix basic hazards.

In Manchester alone, over £8.5 million has been paid out since 2020 in claims against the city council for injuries linked to highway defects. During that time, 1,595 pedestrian accident claims were filed—most involving cracked paving, loose kerbstones, or other dangerous surface issues. Of those, 690 resulted in compensation, showing a clear pattern of liability for poorly maintained footpaths.

And it’s not just broken paving. Other common hazards include slippery floors with no warning signs, steps without ramps or handrails, and dim lighting that makes obstacles hard to spot—especially for people with low vision or mobility aids.

The Health and Safety Executive regularly publishes data on these types of preventable injuries. If you’ve been hurt in a public space, it’s worth checking whether there’s a history of similar incidents or ignored complaints.

When Medical Care Causes Harm

Medical negligence isn’t limited to major surgical mistakes. For disabled people, it often takes the form of being ignored, dismissed, or not given accessible information.

That might include:

- Incorrect treatment due to assumptions about your condition.

- Failure to account for access needs during appointments.

- Miscommunication between departments leading to delayed or missed care.

Medical negligence claims are complex and require both legal and medical expertise—but they are possible. NHS trusts have a duty to provide safe, informed, and accessible care.

Dangerous Products and Equipment Failures

Not all harm comes from people. A defective mobility aid, a broken hoist, or a malfunctioning lift can cause serious injury—and in some cases, long-term disability. If a product hasn’t been tested properly or doesn’t meet safety regulations, the manufacturer or seller can be held responsible.

This includes:

- Items that arrive damaged or faulty.

- Equipment that fails during use, especially where safety is involved.

- Products with no clear instructions or inaccessible information.

You’ll need to keep the product, the packaging, and any proof of purchase if you plan to take legal action.

What To Do If You’ve Been Hurt

If you’ve been injured and are considering making a claim, here’s what to do:

- Get medical help. Your health comes first—go to A&E, call 111, or see your GP.

- Report the issue. Whether it’s your workplace, council, or a business, make a formal report and get a copy.

- Gather evidence. Photos, videos, and witness names can all be critical.

- Keep a record. Write down your symptoms, expenses, and how the injury affects your daily life.

- Ask for accessible formats. This includes medical records, workplace communications, or insurance documents.

- Speak to a solicitor. Look for someone who understands both personal injury and disability discrimination law.

Your Rights Matter

In the UK, the law recognises that harm caused by inaccessibility or discrimination is unlawful—not simply unfortunate. Disabled people have the right to move through public spaces, work safely, and live without avoidable risk. When those rights are breached, legal action can hold those responsible to account.