How to Improve Indoor Air Quality – and Why It Matters for Disabled People

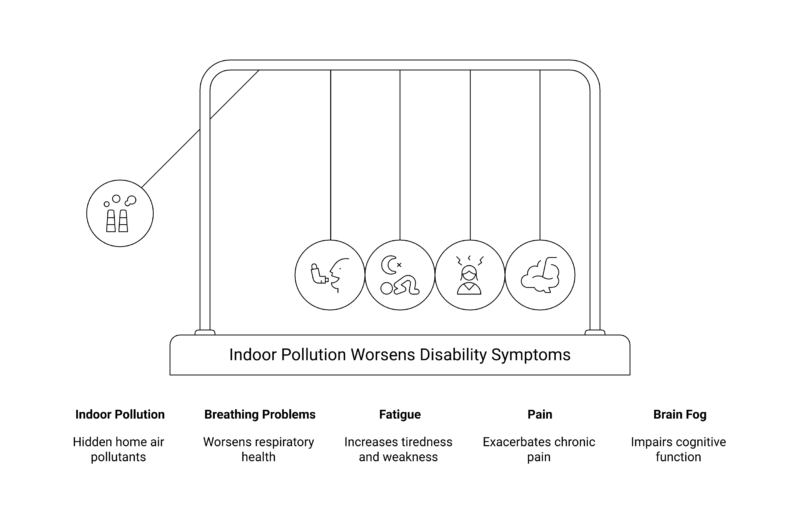

Indoor air quality affects health, energy, and daily functioning, yet it often goes unnoticed. For many disabled people, spending long periods indoors means polluted air can quietly worsen respiratory symptoms, fatigue, pain, and cognitive fog. This article explains why indoor air quality matters more for disabled households, what typically pollutes the air inside homes, and which practical steps — from ventilation to filtration — can make a real difference without adding extra burden.

Key takeaways

| What matters | Why it matters for disabled people |

| Indoor air can be more polluted than outdoor air | Many disabled people spend most of their time at home |

| Poor ventilation worsens damp, mould, fatigue and breathing | These directly affect daily living and independence |

| Ventilation and filtration work together | One dilutes pollution, the other removes it |

| Mechanical systems reduce daily effort | Helpful where windows, energy or mobility are barriers |

| Small changes still help | Even short airing or one purifier can reduce symptoms |

Hidden air, visible impact

A disabled person notices something odd. At home, they wake with headaches, heavy fatigue, or a tight chest. Their concentration slips, and everyday tasks feel harder. When they leave the house — even briefly — some of those symptoms ease. Nothing obvious has changed, yet their body keeps reacting.

Indoor air quality, often shortened to “IAQ”, describes how clean or polluted the air inside buildings is. It includes particles, gases, moisture, and how well fresh air replaces stale air. In the UK and other high-income countries, people spend around 80–90% of their time indoors. For many disabled people, that figure is higher still, especially for those who work from home, use mobility aids, or rely on home-based care.

Large population studies link air pollution exposure to higher rates of disability, reduced ability to manage everyday activities, and worsening long-term health. When the air inside a home is polluted, the effects are constant rather than occasional.

Why indoor air quality matters more for disabled people

Disabled people are often exposed to indoor pollution more intensely and for longer periods. Many spend most of their day in one or two rooms. Some live in housing they cannot easily adapt, including social housing or private rentals where ventilation upgrades are slow or disputed. Energy costs, mobility limits, and safety concerns can all make opening windows harder.

Certain conditions are also more sensitive to poor air quality. Respiratory conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchiectasis can flare with particles, nitrogen dioxide, and damp. Neurological and cognitive conditions, including acquired brain injury, multiple sclerosis, dementia, autism, and attention-related conditions, are linked to changes in air quality that affect concentration, processing speed, and fatigue. Immune-related conditions, including autoimmune disease, myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome, long Covid, and immunosuppression, are often affected by mould, infections, and inflammatory responses triggered by polluted air.

Research consistently shows that indoor pollution is linked to worse respiratory symptoms, more hospital admissions, increased difficulty with daily activities, and reduced cognitive performance. These are not minor effects. They influence whether someone can cook, wash, work, or rest properly in their own home.

What pollutes indoor air – and how it shows up in daily life

Indoor air pollution comes from many ordinary activities. Fine particles are released by cooking, candles, gas or solid-fuel heating, and outdoor traffic that enters through doors and windows. Nitrogen dioxide is produced by gas hobs and heaters. Volatile organic compounds are released by cleaning sprays, paints, aerosols, fragrances, and some new furniture. Damp homes allow mould spores to build up. Carbon dioxide rises when ventilation is poor and people share a space for long periods.

For disabled people, these pollutants often show up as “mystery symptoms”: headaches, sore or dry eyes, coughing, wheezing, dizziness, chest tightness, fatigue, poor sleep, and brain fog. Symptoms may track specific rooms or buildings, a pattern sometimes described as sick building syndrome. The body reacts even when the cause is not immediately visible.

Core strategy one: ventilation

Ventilation works by replacing stale indoor air with fresh outdoor air, reducing moisture and diluting pollutants. It is one of the most effective ways to improve indoor air quality.

Disabled people often face barriers here. Opening windows can be physically difficult, unsafe, or uncomfortable due to temperature sensitivity or energy costs. That does not make ventilation less important; it makes the right approach more important.

Natural ventilation

Short, focused airing can be effective without chilling a home. Opening windows wide for five to fifteen minutes after cooking or showering removes a large amount of moisture and pollution. Cross-ventilation, where air flows between opposite windows or doors, works faster when it is safe to do so.

Where mobility or energy is limited, simple adaptations help. Lever handles, window openers, or support from carers at set times reduce effort. Trickle vents and door undercuts allow air movement even when windows stay closed.

Mechanical ventilation

Mechanical extract ventilation uses fans to remove stale air from kitchens, bathrooms, and wet rooms. Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery goes further by supplying filtered fresh air continuously while retaining warmth. These systems are especially helpful in airtight flats or homes with ongoing damp.

For disabled households, mechanical systems reduce daily workload. There is less need to remember windows, wipe condensation, or manage mould patches repeatedly. Temperature and air quality remain more stable, which matters for people with autonomic symptoms or sensitivity to cold.

Specialist suppliers such as Ventilationland work with homes affected by damp, mould, allergies, and chronic respiratory illness, helping residents and housing providers choose systems that suit real-world living rather than ideal conditions.

Useful tools

Good extractor fans are quiet, powerful enough for the room, and run on timers or humidity sensors. Carbon dioxide monitors offer simple feedback. Readings below about 1,000 parts per million in living spaces usually indicate adequate ventilation. For some disabled people or carers, these numbers make it easier to decide when to air a room or adjust ventilation settings.

The UK Government has produced a useful and extensive guide aimed at householders to explain these issues.

Core strategy two: filtration

Filtration removes pollutants rather than diluting them. It is particularly helpful where outdoor air is polluted or windows cannot be opened easily.

HEPA filters capture fine particles such as dust, pollen, smoke, and some mould spores. Activated carbon filters absorb gases and odours from cleaning products or cooking. Studies in people with respiratory and heart conditions show that HEPA filtration lowers indoor particle levels and can improve symptoms.

When choosing a purifier, disabled people often need low noise, simple controls, and clear maintenance routines. Carers can build filter changes into regular support, reducing cognitive load.

During the pandemic, we bought HEPA air filters for the bedrooms and the rooms where carers were present. At the time, it was about reducing the risk of Covid as much as we could. We still use those filters now, and they’ve turned out to be useful in other ways too. Sleep is better, hay fever symptoms are calmer, and they help clear unpleasant odours in rooms where personal care and changing take place. It’s one of those changes that quietly made day-to-day life easier. – Duncan, Editor

Damp, mould, and moisture

Damp and mould develop when moisture builds up faster than it can escape. They are strongly linked to respiratory problems, infections, and poorer mental health, particularly in low-income and disabled households.

Simple habits help, such as using lids on pans or ventilating when drying clothes. Dehumidifiers can reduce moisture where ventilation is limited. In many homes, though, mechanical ventilation is the only realistic long-term solution. Repeatedly wiping mould treats the symptom, not the cause.

Where mould persists, it becomes a housing and disability rights issue. Tenants are not responsible for structural problems that make a home unhealthy.

UK government guidance recognises that people with long-term health conditions, mobility restrictions, or who spend long periods indoors face higher risks from damp and mould and require urgent action.

Reducing chemical and combustion sources

Gas cooking releases nitrogen dioxide and particles. Using an extractor hood that vents outside, opening a window during cooking, and using back burners reduce exposure. Some disabled people use portable induction hobs to avoid gas emissions entirely.

Candles, incense, smoking, and vaping release large amounts of particles indoors. Reducing use or moving these activities outside lowers risk for sensitive lungs. Cleaning sprays and fragranced products are a common source of irritation. Fragrance-free, ready-mixed cleaners reduce exposure without adding physical work.

Room-by-room priorities

Bedrooms matter because some disabled people need to spend longer there. Ventilation, clean bedding, and placing purifiers near the bed help. Living rooms and home offices benefit from managing carbon dioxide build-up when carers or visitors are present. Kitchens and bathrooms rely heavily on effective extraction to control moisture and combustion pollutants.

NHS guidance on damp and mould links to detailed advice from the Centre for Sustainable Energy, which explains how condensation, poor ventilation and cold homes contribute to mould and respiratory problems.

Working with carers, landlords, and services

Indoor air quality can be part of care planning and occupational therapy assessments. Keeping photos of mould, symptom diaries, and carbon dioxide readings helps when raising concerns with landlords or housing associations. Environmental health services can step in when homes remain unsafe.

Bringing it together

Improving indoor air quality does not require perfection. Small, steady steps — a short airing routine, one well-placed purifier, or a reliable extractor fan — can reduce symptoms and support independence. For disabled people, cleaner air is not about comfort alone. It affects energy, cognition, and the ability to live well at home.

When larger changes are possible, mechanical ventilation systems designed for lived-in homes, can reduce the day-to-day effort of keeping air healthy.