Why Online Therapy Can Remove and Create Barriers for Disabled People

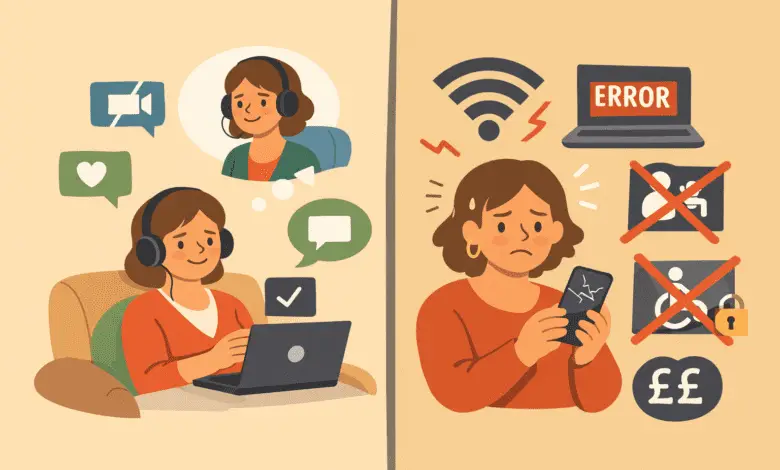

Online therapy is often described as more accessible than in-person support, but disabled people’s experiences in the UK show a more complicated picture. For some, remote sessions remove barriers around travel, energy, and rigid appointment systems. For others, digital exclusion, inaccessible platforms, cost, and a lack of disability-aware therapists create new obstacles. This article looks at online therapy through a disabled-led, social-model lens, drawing on lived experience and UK context to explore when online therapy helps, when it fails, and why genuine access is always about choice rather than trends.

Key takeaways

| What matters | Why it matters for disabled people |

|---|---|

| Online therapy is not automatically accessible | Access depends on design, funding, format choice, and disability understanding |

| Barriers are systemic, not personal | Poor mental health links to poverty, discrimination, and exclusion, not individual failure |

| Flexibility can improve access | Remote sessions can reduce travel, energy use, and missed appointments |

| Digital exclusion is real | Cost of data, devices, skills, and private space can block access |

| Choice is central | Disabled people need options: online, in-person, hybrid, peer support, or none |

1. Introduction: Why This Conversation Needs Disabled Voices

Most writing about online therapy still comes from clinical, tech, or commercial viewpoints. Disabled people are usually spoken about, not listened to. When disabled voices are missing, online therapy gets framed as a neat solution rather than a system that can either reduce barriers or reinforce them.

Online therapy is not automatically accessible or “better”. It can help, harm, or do very little at all. Everything depends on how services are designed, what they cost, whether disabled people can actually get online, and whether therapists understand disability as a social and political reality rather than an individual issue.

2. Mental Health and Disability: The System, Not the Individual

Using the social model, not the pity model

The social model of disability starts from a simple idea: people are disabled by barriers in society, not by their bodies or minds. When applied to mental distress, this shifts the focus away from fixing individuals and towards changing the conditions that cause harm.

In the UK, disabled people experience higher rates of poor mental health than non-disabled people. This is not because disability itself causes distress. It links to poverty, benefit insecurity, discrimination, inaccessible housing, exclusion from work, and services that do not meet disabled people’s needs.

Structural barriers that push many disabled people into crisis include long NHS waiting lists for Talking Therapies, inaccessible buildings and transport, rigid appointment systems, and a shortage of therapists who understand disability without needing constant explanation. None of these are personal failings. They are design and funding choices.

The point here is political rather than tragic. Distress grows where people are boxed in by systems that do not work for them.

3. When Online Therapy Does Improve Access

Practical benefits, grounded in real experiences

For some disabled people, online therapy removes barriers that make in-person support unrealistic.

Travel and energy

Remote sessions can remove the need for accessible transport, taxis, or painful journeys. For people with chronic pain, fatigue, or mobility impairments, this alone can make regular therapy possible.

Flexibility and pacing

Different formats matter. Video, phone, live chat, or asynchronous messaging can help people manage fluctuating energy, brain fog, or speech difficulties. Being able to attend from bed, a darkened room, or with sensory aids changes who can take part at all.

Access to expertise beyond your postcode

Online therapy can make it easier to work with disability-specialist or disabled therapists elsewhere in the UK, rather than being limited to whoever happens to practice locally.

Fewer missed sessions during flare-ups

People with ME, Long COVID, autoimmune conditions, or variable mobility often miss in-person appointments through no fault of their own. Staying at home can mean continuity instead of constant restarts.

Lived experience examples

Wheelchair users and building access

Many psychiatric facilities and therapy offices remain inaccessible to wheelchair users. One Reddit user pointed out that many mental health places are “literally not accessible if you use a wheelchair – stairs everywhere, tiny bathrooms, no thought for us at all.” Meanwhile, a therapist noted that “Telehealth has been a game changer for my disabled clients; a bunch of them literally couldn’t get into my old office because the building had stairs and no lift.” For some wheelchair users this means online sessions are the only realistic way to attend regularly.

People with ME or Long COVID

Post-exertional malaise can make even basic activities impossible. One person with Long COVID described how “If I shower, I can’t also have a phone call that day without crashing. Post-exertional malaise is that bad.” A person with ME/CFS on Reddit explained that “Just getting to an appointment would use up my whole week’s energy budget with ME/CFS,” and another said “The only ‘therapy’ I can manage right now is brief check-ins by phone. Anything longer wipes me out for days.” Some people with ME or Long COVID only tolerate very short or audio-only remote sessions, and would crash badly if they had to travel to a clinic.

Neurodivergent people

For some neurodivergent people, camera-off, audio-only or chat-based therapy reduces masking pressure and sensory overload, and actually makes it easier to engage. One person explained that “Teletherapy is so much better with the camera off. I can actually focus on what I’m feeling instead of staring at my own face and masking the whole time.” A therapist observed that “A lot of my neurodivergent clients do better with the camera off or with just audio. Once I stopped pushing video, their engagement went way up.” Another person with ADHD noted that “Having my camera on absolutely tanks my focus. Turning off self-view and sometimes the camera itself is the only way I can follow Zoom meetings with ADHD.”

These benefits are real. They just are not universal.

4. Where Online Therapy Falls Short for Disabled People

New barriers, same exclusion

Online therapy can also introduce barriers that mirror wider digital inequality.

Digital exclusion and equipment

Many disabled people do not have reliable internet, private devices, or the digital confidence platforms assume. Some rely on pay-as-you-go data or shared phones, shaped by poverty and cuts to social care. Scope has found that many disabled people struggle with basic online tasks because services are not designed accessibly, increasing stress and isolation.

Inaccessible platforms and formats

Common problems include missing or inaccurate captions for d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing users, platforms that do not work properly with screen readers or keyboard navigation, and services that only offer video, excluding people who need phone, text, or asynchronous options.

Privacy, safety, and housing

Online therapy assumes a private space. For people in shared housing, overcrowded accommodation, or unsafe family situations, speaking freely can be impossible or risky.

Sensory and cognitive overload

Video calls can exhaust autistic people, those with ADHD, brain injuries, or stroke survivors. Multiple visual inputs, delays, and seeing yourself on screen can drain energy quickly. Complicated portals and long forms add another layer of exclusion.

None of this is about people “not trying hard enough” to use technology. It is about systems built without disabled people in mind. UK charities including Mind and Scope have repeatedly warned that digital-first mental health services risk widening inequalities when choice and accessibility are not built in.

5. Cost, Funding, and the Reality of “Affordability”

When “cheaper” is still out of reach

Online therapy is often marketed as affordable, yet many disabled people find it remains out of reach.

Private therapy costs

Private therapy in the UK commonly costs £50 to £100 or more per session. Many online platforms still charge weekly fees that add up quickly. For people relying on benefits, social care, or low-paid and part-time work, these costs can be unrealistic.

NHS and low-cost options

Free or low-cost options exist, but each has limits. NHS Talking Therapies are free, yet waits can be long, session numbers capped, and standardised models may not fit complex disability or long-term distress. NHS Talking Therapies treat online and in-person sessions as equivalent in terms of eligibility. You can usually self-refer through your local service’s website, choose phone or video where available, and request adjustments.

What is less clear is how flexible services will be once treatment starts. Session numbers are often capped, and models may be standardised. Disabled people frequently report having to push for pacing, breaks, or alternative formats. If NHS therapy does not fit, that is not a failure on your part. It reflects limits in how services are funded and designed.

Sliding-scale services and community counselling can help, though availability varies widely. Disabled-led counselling schemes and collectives offer important alternatives, but capacity is often stretched.

Hidden costs

There are also hidden costs. Being at home more means higher energy bills. Data, devices, and suitable space are not free. Many disabled people also spend emotional energy educating non-disabled therapists about benefits, housing, access needs, and ableism.

Readers can decide for themselves whether any option is worth the cost. The role of services is to be honest about limits.

6. How to Find Disability-Aware Online Therapy in the UK

Finding therapists who understand disability

Finding online therapy that actually works for disabled people often takes more effort than it should. There is no single NHS-approved list of disability-aware therapists, and many large platforms do not screen for disability knowledge at all. That means the burden often falls on disabled people to search carefully and ask direct questions.

UK places disabled people often start:

- NHS Talking Therapies (England)

You can self-refer online without going through a GP. Many services now offer phone and video sessions as standard, though access and waiting times vary by area. Session models are often structured, so it helps to ask early whether adaptations are possible. - Disabled-led or disability-specialist services

Examples include disabled-run counselling projects, collectives, or individual practitioners who centre disability, chronic illness, and neurodivergence in their work. These services are often smaller, may have waiting lists, and may not look “slick”, but disabled people frequently report feeling safer and less exhausted in these spaces. - Therapist directories with filters

UK directories allow searches by specialism, format, and access needs. Filters to look for include disability, chronic illness, neurodivergence, remote working, and experience with benefits or social care systems.

Tip from lived experience: If a therapist or service does not mention disability access anywhere on their site, that silence is information. It often means you will be doing the educating.

7. Checking Therapist Credentials and Safety

Making sure an online therapist is legitimate

Online therapy lowers barriers to entry, which is not always a good thing. In the UK, “therapist” and “counsellor” are not protected titles, so checking credentials matters.

What to look for:

- Registration with a recognised UK body such as:

- British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy

- UK Council for Psychotherapy

- British Psychological Society (for practitioner psychologists)

- A clear registration number you can check on the organisation’s website

- A UK-based practitioner if you want UK law, safeguarding, and benefits context

Questions that are reasonable to ask before starting:

- What experience do you have working with disabled people or long-term conditions?

- How do you adapt sessions when access needs change?

- What happens if I need to switch format at short notice?

Red flags:

- No registration details anywhere

- Pressure to pay upfront for long blocks of sessions

- Claims that therapy alone can “fix” disability-related distress

- Dismissive responses to access questions

These checks are about safety, not gatekeeping.

8. What Disabled People Say Makes Online Therapy Accessible

A lived-experience checklist for services

Disabled people consistently point to similar factors when talking about what helps.

- Clear choice of formats, including video, phone, voice-only, live text chat, and asynchronous messaging

- Plain-language access statements explaining platforms used, caption options, how adjustments work, and how to request them

- Therapists who understand disability, benefits, housing, social care, and ableism without starting from zero each session

- Flexibility around cancellations, lateness, and switching formats during flare-ups, without punitive fees or judgement

- No pressure around productivity or “pushing through” pain, with space for pacing and rest

- Options to bring a supporter, use chat alongside speech, or turn off self-view

- Transparent information about cost, funding routes, and service limits from the start

None of these are extravagant requests. They are basic access.

9. Technical Access – What Helps in Practice

Making online therapy workable, not just available

Many access problems show up after the first session, when platforms and processes collide with real bodies and lives.

Common access needs and practical adjustments:

- Captions and transcripts

Ask whether captions are human-checked or automated, and whether live chat or text backup is available if audio fails. - Screen reader and keyboard access

Check whether booking systems, consent forms, and session platforms work without a mouse and with assistive technology. - Low-energy options

Shorter sessions, audio-only calls, asynchronous messaging, or shared documents can make therapy possible during flare-ups. - Reducing video strain

Camera-off policies, hiding self-view, and turning off visual effects can reduce fatigue and sensory overload.

If a service cannot answer basic access questions, that is a system issue, not a personal one.

10. How to Decide if Online Therapy Is Right for You

Questions, not instructions

There is no correct choice that fits everyone. These prompts can help people think through their own situation.

- Access and energy: How do travel and being on screen affect your body and mind in different ways?

- Privacy and safety: Do you have somewhere you can talk freely without being overheard or interrupted?

- Tech and format: What communication methods actually work for you, given the devices and connection you have?

- Therapist fit: Do you want a disabled therapist or someone with specific disability knowledge? Are there UK-based specialist services worth exploring?

Red flags

- No mention of disability access or adjustments anywhere on the site

- Video-only rules, camera-on policies, or rigid cancellation terms

- Language that treats disability mainly as a mindset problem

It is okay to try online therapy and decide it is not right for you. It is also okay to change therapist, format, or service without guilt.

11. Data Privacy, Safety, and Control

Who sees your data, and where it goes

Online therapy involves personal data, and disabled people often have specific reasons to be cautious, including safeguarding concerns, benefit assessments, or unsafe living situations.

Basic questions worth asking:

- Is the platform compliant with UK data protection law?

- Where are session notes and messages stored?

- Are sessions recorded automatically, or only with consent?

- What information is shared with third parties, if any?

You have the right to ask these questions without being treated as suspicious or difficult.

12. Alternatives and Complements to Therapy

Therapy as one tool among many

Therapy is not the only route to support, and for some it is not the main one.

Peer support and community

Peer support and disabled-led communities can offer understanding without explanation, whether through online groups, condition-specific forums, or user-led organisations. Disabled-led arts groups, advocacy spaces, and informal hangouts can support mental health indirectly by reducing isolation.

Practical advocacy and support

Practical help matters too. Support with benefits, housing, access needs, and discrimination can reduce distress at its source rather than asking people to cope better with injustice.

Crisis support

For moments of crisis, UK services such as NHS urgent mental health helplines, Samaritans, Shout, and local Mind services can be vital, even while recognising that they are not equally accessible for everyone. Online therapy is not designed for immediate crisis support or situations where someone is at risk of harm. In those moments, crisis lines, urgent NHS services, or local emergency pathways are more appropriate, even though they also have access gaps. Knowing this is about clarity, not discouragement.

13. Conclusion: Access Is About Choice, Not Trends

Online therapy is a tool. Like any tool, it can widen access or deepen inequality depending on how it is designed, funded, and delivered.

Disabled people need real choice: in-person, online, hybrid, group work, peer support, or none of these at all. Choice also includes the right to pause, to say no, or to change direction without being framed as difficult or disengaged.

For me, genuine accessibility would mean services that ask fewer assumptions and more questions, that expect fluctuation rather than treating it as a problem, and that trust disabled people to know what support fits their lives.