Securing Social Security Disability Benefits After a Life-Altering Injury or Illness

Important: This guide is about United States disability benefits, specifically Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and other programs run by the Social Security Administration (SSA). If you are based outside the US, the details here will not apply directly, but many of the barriers described — paperwork overload, delays, and repeated assessments — may still feel familiar.

Applying for Social Security Disability After a Serious Injury or Illness

When a serious illness or injury turns your life upside down, the financial worry that follows can be overwhelming. Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) is meant to be a lifeline during this exact crisis, but let’s be honest — the application process is famously tough. It is a system built on strict rules and specific definitions, and getting through it can feel less like filling out forms and more like finding your way through a complex maze.

It is not just the health condition that makes life harder — the way SSDI is set up can also be disabling in itself. Long forms, repeated assessments, strict rules about work history and documentation, and long waits for decisions mean the people with the least energy, brain space, or digital access often face the biggest hurdles. Instead of meeting you where you are, the system expects you to perform admin marathons while you are already at your lowest.

The Social Security Administration (SSA) has its own rigid definition of “disability.” It does not always match what your own doctor might say. To qualify, you must show that your condition stops you from doing your past work and any other type of substantial work, and that it has lasted — or will last — at least a year.

Lived experience: “The forms were harder than the pain”

“When I finally applied for SSDI after my stroke, the hardest part was not the weakness in my arm — it was trying to explain why I could not get through a ‘normal’ workday anymore. I had to write, over and over, how quickly fatigue and brain fog would hit, and it felt like I was being asked to justify my existence rather than my disability.”

Many disabled people describe the process as adversarial, as if they are being asked to “prove” they are sick enough again and again. That emotional toll sits on top of the physical or mental health impact they are already dealing with.

What Does the SSA Consider a Disability?

The SSA definition of disability is different from what a private insurance company or the VA might use. To get SSDI, you have to show that your condition is severe and long-lasting.

- You cannot do the work you did before your injury or illness.

- You cannot adjust to other types of work because of your health.

- Your condition has lasted or is expected to last for at least one year, or lead to death.

The Blue Book and Medical Listings

Think of the SSA’s “Blue Book” as a very picky checklist. It spells out exactly which medical conditions qualify for disability, but it is incredibly specific. You can read the official adult listings here.

The truth is, plenty of serious conditions do not fit neatly into those boxes. Issues like fibromyalgia, chronic pain, or mental health struggles often fall outside the Blue Book. If yours is not listed, the approach has to change. Rather than just checking boxes, you have to show how your symptoms — the fatigue, the pain, or the brain fog — limit you just as much as a listed condition.

Getting Started: The Importance of a Strong Foundation

You can apply online, by phone, or at your local SSA office. No matter the path, it is a heavy lift. You will need your full medical history, a 15-year job list, and every treatment record you can find. Just one tiny error or a forgotten date can cause months of delays.

For many people, the barrier is not “motivation” but inaccessible processes: long phone wait times, online forms that are not screen-reader friendly, dense legal language, and offices that are difficult to reach if you are housebound, do not drive, or rely on paratransit.

Because the rules are complex and the paperwork load is heavy, many people look for help with their application or appeal. In Michigan, that might look like reaching out to a local team like The Clark Law Office in Lansing. Support can come from:

- Legal aid or nonprofit disability law centers, which may offer free or low-cost representation depending on your income.

- Disability rights organisations and charities that provide benefits advice or advocacy.

- Peer support groups, online communities, or local disability organisations where people share what worked for them in real life.

- Private attorneys or paid advocates who focus on SSDI cases, usually working on contingency (they are paid a capped fee from your back pay if you win).

If you do choose a lawyer or advocate, treat them as one option among many: ask about fees, experience with your type of condition, and how they will communicate with you. No single firm is the “right” answer for everyone.

Your Medical Evidence: The Heart of Your Case

Your medical records are everything. A diagnosis alone is rarely enough. The SSA needs to see how your symptoms translate into real-world limitations. Gather everything:

- Contact information for every doctor, specialist, and clinic.

- Copies of all test results (MRIs, blood work, X-rays).

- A detailed work history describing the physical and mental demands of your past jobs.

- Statements from people who see your daily struggles.

What disabled applicants say helped most:

- Keeping a daily symptom and activity diary, including how far you can walk, sit, concentrate, or interact on a typical bad day.

- Getting a detailed Residual Functional Capacity (RFC) form from a specialist who knows you well, not just a one-off visit.

- Bringing someone with you (in person or on the phone) to help remember details and speak up if you shut down under pressure.

The Role of the RFC Assessment

The SSA uses a “Residual Functional Capacity” (RFC) assessment to understand your abilities. This form asks your doctor to rate your physical and mental abilities, including how much you can lift, how long you can sit or stand, how well you concentrate, and how often you would need breaks or time off-task.

Real-World Complications the Forms Do Not Show

- Fluctuating capacity. You might manage a few “good days” and then crash for a week. SSA looks at whether you can sustain full-time work consistently, not whether you can push through occasionally.

- Neurodivergent communication. If you are autistic, ADHD, or otherwise neurodivergent, forms and phone calls can be overwhelming. You may need support to break tasks down, request written communication, or have someone attend a hearing with you.

- Part-time, gig, or informal work. Many people have patchy histories, cash-in-hand jobs, or caregiving gaps. You can still apply; just be honest and detailed about what you did, how often, and why you had to stop.

- Language, literacy, and digital barriers. If English is not your first language, you struggle with reading, or you lack internet access, you may need help filling in forms, asking for interpreters, or using SSA’s online services.

These are structural issues, not personal failings, and they are part of what makes the system inaccessible for many disabled people.

What to Expect: Exams and the High Chance of Initial Denial

The SSA may request a Consultative Examination (CE) with a doctor they choose. Be honest and thorough about your symptoms during this appointment; downplaying your pain or fatigue can seriously hurt your claim.

Initial denials are common and often reflect gaps in paperwork, not a judgment on whether you are “really” disabled. Common reasons include earning over a set limit, insufficient medical evidence, or an assumption that your condition might improve too quickly.

“For me, the first denial felt like the system was calling me a liar. I had years of medical records, but the letter just said they didn’t see enough evidence. It took another psychologist’s report and a hearing before a judge for Social Security to finally accept how disabled I really was.”

The Appeals Process: Your Path Forward

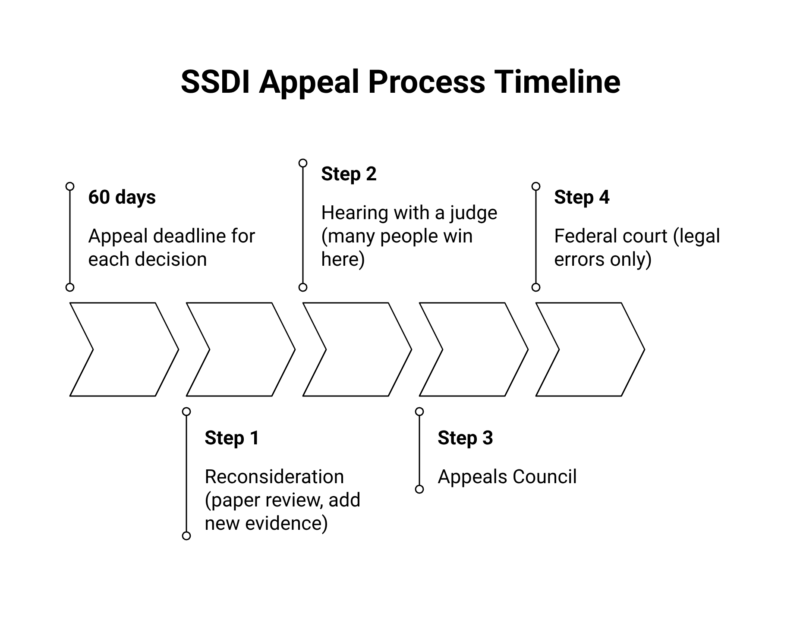

If you receive a denial, you have the right to appeal. You typically have 60 days from the date on the denial letter to request the next step. The SSA’s overview of the appeal steps is here.

- Reconsideration. A fresh review of your file by a different decision-maker. You can and should submit new evidence here.

- Hearing before a judge. You speak directly to an administrative law judge. A vocational expert may testify about jobs in the economy.

- Appeals Council and federal court. These stages focus on legal or procedural errors rather than re-arguing every detail of your health.

High denial rates, long waits, and repeated reviews are built into the system and can push people into debt, unsafe housing, or going without treatment while they wait.

Special Considerations for Mental Health and Chronic Pain

Not all disabilities show up on an X-ray. If you live with depression, PTSD, anxiety, chronic fatigue, or fibromyalgia, your case is handled differently. The SSA looks for “marked limitations” in your ability to function day to day.

Keeping a journal that tracks your sleep, pain, energy, panic attacks, flashbacks, or shutdown days can be very helpful — and it can support what ends up in your medical records.

Understanding the Financial Side of SSDI

The amount of money you receive depends on how much you have worked and paid into the system through Social Security taxes. It is not based on how severe your disability is.

The Waiting Period

There is a five-month waiting period from the date your disability started before you can receive monthly payments. Because the application process can take longer, some people receive back pay once approved.

Health Insurance

Once you have been on SSDI for 24 months, you become eligible for Medicare. The SSA explains the 24-month Medicare waiting period here.

Moving Forward with Confidence

Applying for disability is slow, often discouraging, and can feel like a full-time job on top of your health. But this is not a handout. You have been paying into this insurance with every paycheck for years, and now that you need it, it is your right to access that support.

Take it one form at a time: gather your records, double-check your paperwork, and mark every deadline on the calendar. If you get a denial — and many do — do not see it as the end; see it as the next step.