Why Lived Experience Makes Disabled Speakers Powerful Motivators

Disabled speakers bring powerful insight to workplaces because their expertise is grounded in lived experience. This Easy Read article explores how credibility, inclusive leadership, and psychological safety connect to real organisational change — supported by peer-reviewed research and examples from Disability Horizons contributors.

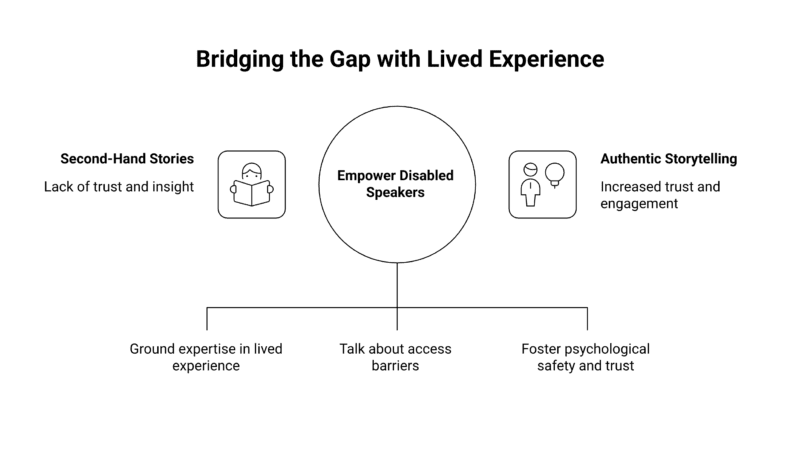

Audiences can tell when a story is second-hand. They notice the difference.

There is a big gap between repeating a lesson and sharing real life.

That gap affects trust.

As Martin Warrillow says in Stroke survivor turned blogger, public speaker and podcast star:

“I’m living, breathing proof that a stroke can happen to you, whatever your age, whatever your state of health.”

When inspiring speakers with disabilities share lessons from their own lives it is because:

They have worked in offices and public places that did not meet their needs.

They have faced systems that made daily life harder.

When they talk about access barriers, they mean real obstacles.

For example, steps at an office door or no captions on videos.

When they talk about hiring, they speak from experience.

They describe interviews, workplaces, and team culture they know well.

Lived Experience Builds Credibility

Credibility means people believe and trust you.

It is not only about confidence.

It is about how you learned what you know.

When someone’s life matches their message, people listen more closely.

Glenda Watson Hyatt explains this in From a speech impairment to a motivational speaker:

“I was heard for the first time. I was no longer invisible, no longer silent.”

When a wheelchair user talks about steps at work, the issue feels real.

It is not just an idea.

When an Autistic professional talks about strict communication rules, the topic becomes practical and clear.

Research shows that many people still have wrong ideas about disabled workers.

Some people think disabled workers cannot do certain jobs.

Often, the real problem is the workplace design or attitudes.

It is not the person’s ability.

Martin Warrillow also says:

“If reading it makes one more person aware of how common stroke is and the harm it causes, I’m happy.”

This clear purpose helps people trust him.

Motivation Rooted in Inclusive Leadership

Many leaders talk about inclusive leadership.

Inclusive leadership means leading in a way that includes everyone.

It means people feel valued and able to speak up.

Research links inclusive leadership to higher psychological safety.

Psychological safety means people feel safe to share ideas.

They do not fear blame or punishment.

Teams often perform better when people feel safe.

Disabled professionals can explain what this looks like in real life.

They can describe job adverts that left people out.

They can share stories about managers who changed meeting formats.

Simple changes, like sharing notes in advance, can help everyone join in.

Platforms such as PepTalk’s disability motivational speakers page list speakers and booking details.

Any results or business claims on that page are the platform’s own reports.

They are not separate academic studies.

Disabled speakers are not only talking about challenges.

Many are business owners, advisers, researchers, and leaders.

Their disability shapes their view.

Their professional skill stands on its own.

A Catalyst for Cultural Change

A strong keynote can shape decisions.

When disabled speakers explain how systems block access, people see the bigger picture.

They see that barriers come from design choices.

They see that organisations can change those choices.

Martin Warrillow says:

“Standing in front of a room full of people and telling them my story is fun for me and educational for them.”

Stories on Disability Horizons, including

Knocking down disabling barriers through positivity,

Souleyman Bah on The Apprentice, and

Amberly Lago: disabled fitness trainer and motivational speaker

show how lived experience links to leadership and business success.

Many disabled professionals build strong problem-solving skills.

They often adapt to systems that do not fit them.

These skills matter in mainstream leadership.

How to Work with Disabled Speakers Well

If organisations want real impact, they need to plan well.

Pay speakers for preparation time and delivery.

Talk about access needs early.

Do not describe someone as inspirational only because they are disabled.

Ask for clear actions people can take after the event.

For example, review hiring steps.

Check building access.

Improve meeting formats.

Disabled speakers are not token guests.

They can help create real workplace change.

Treat them as experts.