Inclusive Dental Care in the U.S.: How Dentists Treat Pulpitis and Why It Matters for Disabled Patients

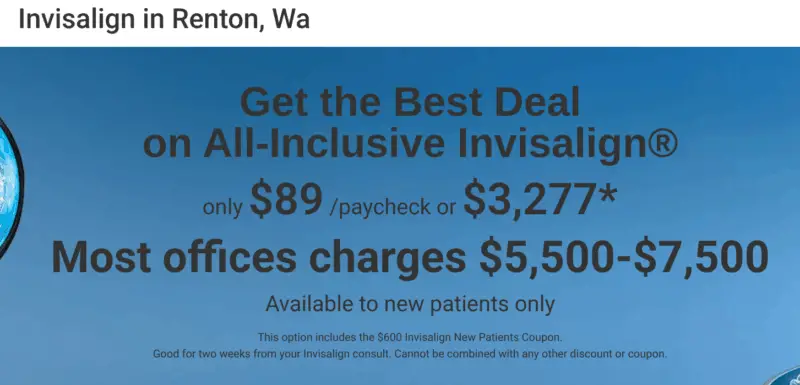

This article was submitted by Invisalign Renton Dental Studio in Washington State—an ADA-compliant practice committed to accessible, patient-centered care. Their clinic includes a wheelchair-accessible car park, step-free entrance, and an accessible restroom, ensuring that disabled patients aren’t met with physical barriers before treatment even begins.

With experience treating patients with diverse access needs, the team at Renton Dental Studio shares how pulpitis is diagnosed and treated—and why inclusive dental care matters, especially for disabled adults using a system that often overlooks them.

Summary:

Inflammation of the tooth’s pulp—known as pulpitis—can be painful and, if untreated, lead to tooth‑loss or infection. For disabled patients in the U.S., this condition raises unique access and accommodation issues: physical accessibility of dental practices, sensory and communication considerations, insurance and Medicaid barriers, and clinic culture. This article explains what pulpitis is, how it’s diagnosed and treated, and how dental professionals and patients can work together to ensure equitable, effective care.

| Key Takeaways | |

|---|---|

| Understanding the condition | Pulpitis is inflammation of the soft tissue inside a tooth; early (reversible) pulpitis can often be saved with a simple filling, but late (irreversible) pulpitis often requires a root canal or extraction. |

| Barriers for disabled patients | Disabled adults in the U.S. are more likely to face delayed or unmet dental care due to physical access, communication issues, insurance/Medicaid limitations, and provider training gaps. |

| Diagnosis & treatment path | After confirming pulpitis (via clinical exam, vitality testing, x‑rays), treatment depends on severity: for reversible – remove source of irritation + filling; for irreversible – root canal or extraction. |

| Accommodations matter | For disabled patients the usual pathway may need adaptation: longer visits, sensory‑friendly environment, wheelchair access, communication support, insurance flags. |

| Prevention and empowerment | Because disabled people may face greater barriers to routine preventive care, it’s even more important to emphasise early intervention, tailored home care, adapted tools and proactive scheduling. |

What Is Pulpitis and Why It Matters for Disabled Patients

Pulpitis describes inflammation of the dental pulp—the innermost tissue of a tooth that contains nerves and blood vessels. In essence, when decay (a cavity), trauma (such as a crack), or repeated restorations irritate or infect the pulp, it can become painful and eventually necrotic (die).

Dentists distinguish two broad forms:

- Reversible pulpitis – the pulp is inflamed but still salvageable. The pain is usually stimulus‑based (e.g., cold or sweet), and subsides quickly when the stimulus is removed. ([MSD Manuals][1])

- Irreversible pulpitis – the damage is too advanced, the pulp is inflamed beyond recovery, there may be spontaneous pain, lingering heat sensitivity, or sensitivity when biting. At this point, root canal therapy or extraction is usually required.

For disabled patients, the stakes can be higher. Reasons include:

- Delays in accessing dental care (due to mobility, transport, provider shortages) mean conditions like pulpitis may be more advanced by the time they’re treated.

- Sensory or communication differences may reduce early reporting of pain or sensitivity, meaning early reversible pulpitis may go unnoticed until it becomes irreversible.

- Some disabilities or medications may increase risk (dry mouth, difficulty brushing/flossing, high caries risk) meaning pulpitis may be more likely.

Because the underlying cause is a barrier (access, accommodation), rather than the individual, this is a classic case for applying the social model of disability: the condition is the same—but by removing access barriers, we improve outcomes.

How Dentists Diagnose Pulpitis (and Why There Are Extra Considerations for Disabled Patients)

Diagnosis of pulpitis follows standard steps, but when treating disabled patients, dental practices may need to adapt how they perform each step. Here’s how it typically works:

Standard Diagnostic Steps

- Clinical history and symptoms: ask about pain triggers (cold, heat, sweets), whether the pain lingers, if there’s sensitivity when biting or resting.

- Clinical examination: look for deep decay, cracks, large restorations, swelling, gum changes.

- Pulp vitality tests: cold or heat stimulus, electric pulp tester. A non‑responsive pulp may suggest necrosis.

- Radiographs (x‑rays): checking for deep caries, periapical radiolucency (sign of infection), bone changes.

Additional Access & Accommodation Considerations

For disabled patients (physical, developmental, sensory, communicative), the following adjustments can make diagnosis more equitable:

- Ensure physical accessibility: wide doorways, wheelchair accessible dental chairs (or ability to treat patients in their wheelchair), transfer support. The absence of this is a known barrier.

- Allocate longer appointment times: more time to explain procedure, allow for communication support, adapt to sensory needs (e.g., ear sensitivity, noise sensitivity).

- Use communication‑adapted approaches: plain language, visual supports, augmentative communication if needed. Some patients may have difficulty identifying dental pain.

- Prepare for behavioural or sensory needs: some disabled patients may require preparatory visits (desensitisation), quiet rooms, weighted blankets, or sedation options.

- Select a dentist who is either trained in special‑care dentistry or who is willing to make accommodations ahead of time. A major barrier is simply offices not being prepared.

In short: diagnosing pulpitis in a disabled‑friendly way is the same medical process—but the environment must be accessible and the team prepared for accommodations.

What Early Treatment Looks Like When It’s Accessible

If pulpitis is caught at the reversible stage, the dentist’s goal is to remove the cause of irritation and preserve the pulp vitality. Here’s how that looks — and how disabled patients may need extra support.

Standard Early Treatment

- Remove the cavity or irritant (e.g., replace a failing restoration, remove cracked enamel).

- Place a proper restoration (filling) or pulp‑cap procedure to protect the pulp.

- Sometimes place a temporary filling or sedative treatment until full restoration is possible.

- Emphasise preventive care: improved oral hygiene, diet, control of grinding or bruxism if applicable.

Accessible Care Considerations

For disabled patients:

- Schedule longer visits so that adaptation and explanation occur thoroughly and no rushed care.

- Use adaptive home‑care tools: enlarged toothbrush handles, floss holders, electric toothbrushes, mouth‑rinses suited for people with dexterity impairments.

- Arrange transportation or companion support: many disabled patients rely on caregivers or accessible transport; a delayed or missed visit can mean worsening from reversible to irreversible.

- Consider sensory‑friendly modifications: dimmed lights, headphone music, predictable sequence of treatment, sensory cues.

- Ensure insurance/Medicaid acceptance and pre‑visit verification of accommodations—some practices do not feel able to treat disabled patients.

By catching and treating pulpitis early in an accessible way, we preserve the tooth and reduce the need for more complex (and costly) procedures.

When You Need a Root Canal: Keeping the Process Inclusive

If diagnosis shows irreversible pulpitis (or if reversible pulpitis was missed and progressed), the standard of care in the U.S. is often root canal therapy (endodontics) or extraction in certain cases. ([Colgate][9]) For disabled patients, the journey through this process can include additional barriers—but also opportunities for inclusive practice.

Standard Approach

- Remove the inflamed pulp from the root canals, disinfect, shape, and fill the canal with gutta‑percha or other sealant material.

- Restore the tooth with a crown (often) to protect it and restore function.

- If the tooth cannot be saved or the patient declines, extraction + replacement (bridge, implant, denture) is considered.

Inclusive Care Considerations

- Sedation or general anaesthesia may be required for patients with significant mobility, behavioural or sensory considerations. practices should be prepared.

- Accessibility of specialty care: Many endodontists or prosthodontists may not have facilities adapted for wheelchair users, or those needing longer chair time.

- Insurance/Medicaid coverage: Some disabled adults rely on Medicaid, which in many states provides limited dental coverage for adults. ([macpac.gov][6])

- Higher risk of complications: Because disabled patients may have delayed care and comorbidities, close coordination with medical providers is essential (for example if they have conditions affecting healing or are on medications).

- Consent and communication: Ensure that the patient (or their support/caregiver) fully understands what the procedure entails, especially if communication differences exist.

- Time for extra support: Allow for extra time pre‑ and post‑procedure to assess accessibility, transportation home, and any support needed for after‑care.

When this higher‑level care is delivered in an accessible, respectful way, disabled patients can achieve the same outcomes as other patients—but too often systemic barriers undermine that.

How to Protect Against Pulpitis When Routine Care Isn’t Easily Accessible

Because disabled patients often face greater barriers to regular dental care (transport, cost, provider readiness), prevention becomes all the more important. Here are proactive strategies.

Home & Routine Prevention

- Brush at least twice daily and floss/clean between teeth daily. Adapt toothbrush or flossing devices as needed for mobility or dexterity limitations.

- Use fluoride toothpaste and consider mouth‑rinses if appropriate.

- Avoid frequent sugary or acidic snacks/drinks which increase decay risk.

- If you grind your teeth (bruxism) or have restorative work, ask your dentist about a night guard.

- Alert your dental provider immediately if you notice sensitivity to hot/cold, lingering pain, or biting discomfort. Early symptoms of reversible pulpitis should trigger prompt care.

Making Routine Visits Work

- Let your dental office know in advance about any mobility, sensory or communication needs you have so they can allocate time, equipment or adapt their environment.

- Ask whether the dental practice accepts your insurance or Medicaid, and whether they have experience treating patients with disabilities.

- Seek out special‑care dentistry clinics or dental schools with accommodations and training in treating disabled adults. For instance, clinics may offer wheelchair‑accessible equipment or sensory‑friendly rooms.

- If you can’t easily access a full dental practice, look into mobile clinics, community health centres, or services that specialise in adult patients with disabilities.

Advocacy & Systems Change

- Because systemic barriers exist (provider training gaps, low Medicaid reimbursement) disabled adults have higher odds of needing emergency dental care.

- Ask your dentist or local dental association about training in special‑care dentistry and what adaptations they offer.

- Encourage your state dental board or advocacy groups to include accessibility standards for adult dental care (e.g., longer appointment times, physical access, sensory accommodations).

By combining thoughtful home care, smart preparation, and selecting accessible dental providers, disabled patients reduce the risk of pulpitis and its more invasive consequences.

Real Solutions: What Inclusive Dental Clinics Can Offer

Here are some practical features that dental clinics should ideally offer if they aim to serve disabled patients effectively:

- Wheelchair‑accessible operatories with transfer equipment or ability to treat patients in their own wheelchair

- Extended appointment times and scheduling flexibility

- Sensory‑friendly environments: quiet waiting rooms, dimmable lights, headphones/music, communication aids

- Staff trained in disability awareness, communication strategies and inclusive care

- Accepts Medicaid or offers sliding scale for financially vulnerable patients

- Pre‑visit surveys to ask patients about access needs, mobility, sensory triggers, and preferred communication style

- Collaboration with caregivers/support persons when needed (while respecting the autonomy of the adult patient)

When you find a clinic that checks these boxes, you’re far more likely to get prompt, effective care for conditions like pulpitis before they escalate.

Final Thoughts: Accessible Dentistry Shouldn’t Be a Luxury

In a country like the U.S., many disabled adults still face significant barriers to what for others might be straightforward dental care. The condition Pulpitis may start simply, but for disabled patients, delays or inadequate access push it into more complex, costly treatment. By reframing dental care around removing barriers—physical, sensory, communication, financial—we move from “how can the disabled patient cope?” to “how can the dental system adapt?” That shift embodies the social model of disability, and aligns with the ethos of Equip‑Able and Disability Horizons.

If you’re a disabled adult or caregiver reading this: don’t wait for pain to force action. Ask your dental provider upfront: “Are you ready to treat me with my access needs in mind?” If the answer isn’t clear, keep searching. Your health, autonomy and comfort matter.