Viewing disability and difference through the eye of a lens

This is an updated post from our archives. Photographer Claire Gilliam shares her 15-year journey of using self-portraiture to explore and accept her disabled body, challenging societal norms of beauty and normality.

Exploring Disability Representation in Contemporary Photography

In recent years, the portrayal of disability in photography has evolved, with artists using the medium to challenge stereotypes and promote inclusivity. Notable initiatives include:

- Disability Visibility Project: An online community dedicated to creating, sharing, and amplifying disability media and culture. Learn more.

- Disability Arts Online: A platform offering resources and showcasing work by disabled artists. Explore their content.

- Changing the Face of Beauty: A campaign advocating for equal representation of disabled people in media and advertising. Get involved.

These efforts highlight the importance of authentic representation and encourage a broader understanding of disability through the lens of contemporary photography.

Photography: A Tool for Self-Acceptance and Empowerment for Disabled People

Photography can help disabled people feel proud of who they are. By taking photos that show their lives and views, they can challenge stereotypes and share their unique stories.

Photography as a Way to Accept Yourself

Express Yourself and Feel Empowered

Photography lets disabled people share their feelings and thoughts through pictures. It gives them a way to show their world. Taking and sharing meaningful photos can make them feel strong and capable. This can help them feel proud of themselves and build self-confidence.

Find out more about photography as a creative outlet: https://www.ablevoices.org/why-photography.

Breaking Stereotypes

Photos taken by disabled people can challenge how society sees disability. By showing mobility aids or disabilities openly, these photos can change the story. They can show disability as something to respect, not something to pity.

Learn how photography challenges stereotypes: https://www.transportforall.org.uk/news/through-a-different-lens-my-experience-as-a-disabled-photographer-working-with-transport-for-all/.

Photography as Therapy

Taking photos can help with emotions and mental health. For some disabled people, it is a calming and healing activity. It can help process hard feelings and boost happiness by releasing dopamine, a “feel-good” chemical.

Read more about the healing power of photography: https://blog.sigmaphoto.com/2023/through-an-inclusive-lens-photographing-people-with-disabilities/.

Resources for Disabled People Interested in Photography

The Disabled Photographers’ Society (DPS)

The Disabled Photographers’ Society offers support for disabled people in the UK. They provide:

- Free advice and technical help.

- Equipment loans and adjustments.

- Competitions held four times a year.

- Workshops to improve skills.

- An online community to share and learn.

Visit their website to learn more: https://www.the-dps.co.uk.

Adaptive Equipment for Photography

Special equipment makes photography easier for disabled people. Tools like adaptive cameras and mounts can help people with physical challenges enjoy photography.

Find out about adaptive photography tools: https://www.ablevoices.org/why-photography.

Therapeutic Photography Sessions

Some photographers, like Tosha Gaines, offer special sessions for disabled people. These sessions are calming and focused on personal goals. They create a safe space for self-expression.

Learn more about therapeutic photography: https://blog.sigmaphoto.com/2023/through-an-inclusive-lens-photographing-people-with-disabilities/.

Community Photography Classes

Local centers, art schools, or disability groups often run photography classes for disabled people. For example, City Lit in London offers a photography course for people with learning disabilities.

Find out about City Lit’s courses: https://www.citylit.ac.uk/courses/photography.

Original post follows:

Photography can be a powerful way to explore both the human body and how is is seen by the world. Photographer Claire Gilliam talks to Disability Horizons about how she has used it to understand and accept her disability.

I’ve been photographing myself for over fifteen years. Perhaps that sounds rather narcissistic. However, I am not taking photographs to admire myself. In the beginning, the photographs were just self-portraits, but over the years they have evolved into something more complex; they have become a way of describing my own disabled body and helping me understand my relationship with society’s view of ‘normality’.

When you live in a disabled body, it can be difficult to reconcile the image that you may have of yourself with the expectations and perceptions constantly being presented to us by the media. As a visual artist, I felt it was important to explore these issues of body image, in particular, the idea of desirability and difference, and for me, the camera is the perfect ‘eye’ through which I can see myself just as other people might.

I have what is termed as right-sided Hemiplegia, a semi-paralysis and weakness of my entire right side that causes me to walk in a manner that suggests I might topple over at any moment. The sound of my footfall, heavy on the right foot, out of sync with the norm, means you can hear me coming a mile off.

My disability is thanks to a severe head injury from a car accident I was involved in as a baby. I was fortunate in many ways. As the only survivor of my immediate family, it could have easily turned out very differently. But as those closest to me will tell you, I am extremely stubborn when it comes to getting my own way and I suppose my tenacity won out over any poor medical prognosis.

I am able to do almost everything I would like to do (except ride a bicycle because my balance is off) and as I was so young at the time of the accident and have known no different, I’ve grown used to this body of mine; wonky, scarred, unsymmetrical and seemingly out of the ordinary though it may be. I have even, dare I say it, grown to like it despite all the discomforts and physical limitations I have, for this body makes me who I am.

I’ve not always felt this way. As a child at a small all-girls school, I experienced my fair share of bullying. As a teenager, when others were starting to get into relationships and later, exploring their sexuality, I began to feel my difference as a woman. I felt as though people thought; “she is a lovely girl, but not really someone to be fancied”. Yet I had the very same desires and longings as any other ‘normal’ person, and if I’m honest, the constant rebuffs I experienced back then did chip away at my confidence and self esteem.

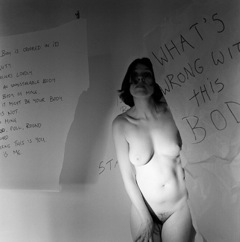

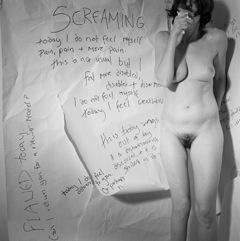

I decided then to turn the camera on myself to explore and question society’s notion of the ‘perfect body’. The experience of making the pictures is a very private and intense one since no one is with me when I work. It’s just my camera, a tripod and me. It can get very physical, sometimes painfully so, as I push myself to understand the physicality and limitations of my body.

I cannot see what I am doing, I just feel it and keep my fingers crossed that I’ve captured something for the camera. The emotional resonance I aim for in the pictures is due, perhaps most importantly, to the way I print them in the darkroom. I choose to be naked so I can be fully honest and truthful in the pictures I make. This is a human body and after years of having people stare at me as I walk by, I feel I am finally giving my permission to look.

My latest portfolio, a work in progress, is entitled This is You, This is Me and incorporates handwritten text with the imagery. These words and thoughts, which are both my own and those uttered by other people, record and reflect upon my experience as a disabled woman.

Even though I am approaching this work from a very personal point of view, I am hoping that there is universality to the subject and imagery that others can relate to. Mainly, I hope that my work challenges and gets people to question their own beliefs of beauty, disability and the ideal body, in order to enable a wider, positive discussion about difference and body image.

You can view more of my work, and explore my world via my website.

By Claire Gilliam

I understand Your feelings about The Stare’s seems like more adults do that than Kid’s ? I am a Amputee on My right leg below the knee from a motorcycle accident in 1986. My Nickname was Tilt ‘LOL’ I tilt sometimes like I am going to fall over. in the Summer I like to dress in Shorts ,and since I’m the old fashion type Its Cut Offs ‘Jean Shorts’, I used to get Sarcastic to people and say things like are My Balls Hanging Out ? WTH are You looking at Man??? lol Keep up the Nice work ,I am a self taught photographer that Really likes Ansel Adams work and Methods, Looking to buy a New 35mm Film Camera this year as I have 3 DSLR’s now . PEACE Garry (y)

We’re all taught it’s “not polite” to stare. But I am always curious about peoples’ “differences”. I think I also want to know if it’s permanent… Dunno why. But I am SO honored that you have revealed yourself in the text above. We all have scars. Yours is always visual. And auditory! We are all strangers, in a way. But now I know you a little more.

Black and white is a perfect vehicle for work. And I marvel at your having/using a darkroom!

Will see you and your work at your very welcome show at Conscious Fork this month!!!