Disability and intimacy: learning to love your body

We all need a level of intimacy – being able to talk, touch, hold hands, hug, kiss or even be sexual. For many disabled people, intimacy is something that they miss out on. But intimacy can mean so much more than just sex. 80-year-old Jonathan, who has cerebral palsy, shares his experiences of how loving your body and finding closeness that works for you can be just as valuable.

Intimacy, noun: ‘close familiarity or friendship,’ ‘a cosy and private or relaxed atmosphere’ and ‘sexual intercourse.’

To me, intimacy is communication of the closest, most personal kind, often without words.

Everybody has a need for intimacy. But where does it begin? What is its essence? Surely it’s the complete acceptance of who you are when you were young? A parent caring for their child, strengthening their unbreakable bond.

As we grow, we establish our own strong identity. We cautiously seek acceptance from others of who we are, carefully revealing more where there is a mutual attraction and a feeling of safety.

However, this is very rarely a smooth and easy process. A myriad of circumstances and personal traits build fears, insecurities and compulsions. Underneath a tough exterior, there may be aching voids of need, loneliness and feeling unaccepted, especially if you have a disability.

Learning to accept your disability

Over the years I have learnt that knowing and accepting yourself is a good way to start to become intimate with other people. It is a back and forth process, discovering yourself a little and then, after becoming more confident, seeking to discover someone else.

But if you’re disabled, there can be more barriers to intimacy, both mental and physical, maybe having less confidence in yourself and not being comfortable with your body and disability. The key to intimacy is changing that.

A mirror is a great device. Your face is a window to your mind. Study it. Understand whatever you find there and, in understanding it, love yourself. Through this, you’ll learn to ‘read’ the faces of friends and relations. If you have little or no sight, do something similar with your other senses, through touch.

Study yourself naked, and your partner, if you have one and they’ll let you. There’s no need to be embarrassed or fearful. If certain things about your body make you uncomfortable, have a good, honest look until they and their function (or even a dysfunction) become part of the whole amazing animal we each are.

Your body is your tool with which to live. The details are fascinating, the whole thing is splendid as it moves and flexes. I’m disabled and getting old, so I’m twisted and wrinkled. It makes no difference to how I feel about myself. Catching glimpses of myself hurrying to bed is a gentle reminder to take care of myself. This body is all I have.

Confidence, noun: ‘a feeling of self-assurance arising from an appreciation of one’s own abilities or qualities.’

Using art to learn to love your body

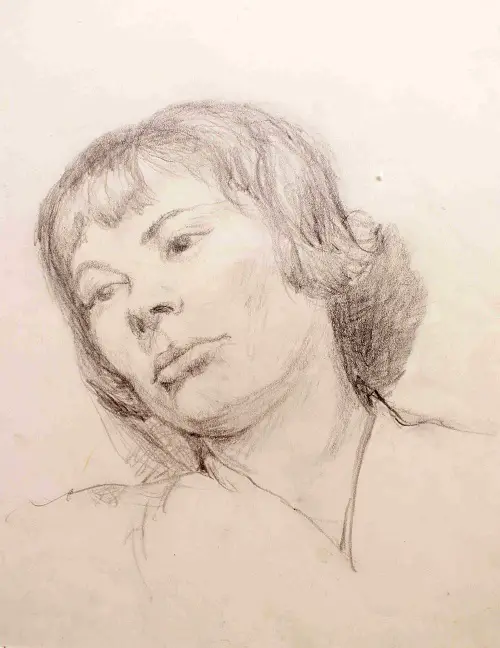

Painting portraits, which I do regularly, is an incredibly intimate thing. Studying the head and face so closely, reading its history, observing the person’s intelligence and emotions, is deeply intimate. My subjects can find it uncomfortable at first. But I match this intimacy with respect, and they regain confidence.

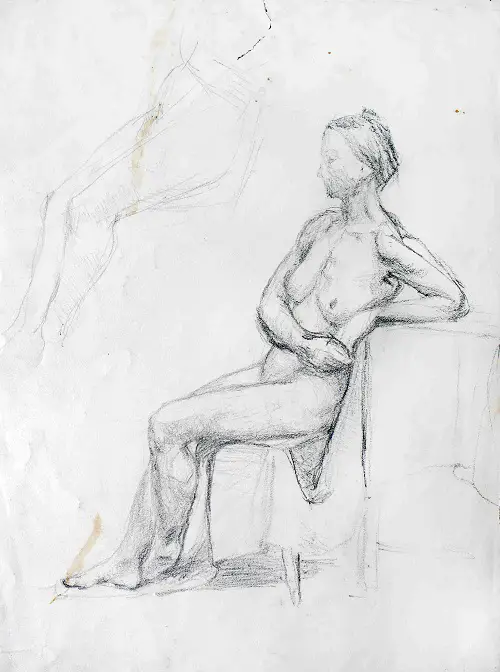

I also love drawing and painting people naked. I’ve mostly done this in art classes, using professional models, but also with one or two friends who have felt safe and confident enough to pose for me. I’m deeply privileged by this trust and mutual respect.

Some people just seem to see and paint shapes. But what fascinates me are the bones, muscles, flesh and fat. The movement, weight, and life in that person, expressed in that body. Be it strength, pose, eagerness, or vulnerability, sometimes I catch a trace of it in my work. It can never be a patch on reality, but it is an intimate blend of them and me on paper.

Intimacy doesn’t have to be conventional

A number of years ago I shared my bungalow with a friend for a year. A small, dynamic and lesbian, she walked with two sticks, drove a tiny car and taught at a college. Living together, sharing laughter and little intimacies, meant we grew close.

Neither of us had been intimate with anyone for some time, and we’d missed that closeness. So, one night, she asked to sleep with me. It wasn’t sexual, it was about feeling wanted. She lay in my bed, safely wrapped in pyjamas, so I tucked myself closely around her. Nothing else was done and nothing was said.

By that summer, I’d started waking her in the mornings when she had an early class, lifting her duvet, helping her sit up on the edge of the bed and silently cuddling, skin to skin. That was an exceptionally uncomplicated physical intimacy – no compulsions, no expectations, no performance, just briefly sharing our physical humanity.

I am glad I felt honest enough to be so unconventional and get so close. It did not happen out of the blue, of course. So, although it slightly startled the first time I did it, she already knew she was safe with me and that I respected her. When she died years later of MS, part of her funeral was dedicated to my our relationship.

Finding intimacy where you feel comfortable

Such a simple closeness was a long way from the complexity of sexual intimacy. The mutual and conflicting passions, needs and urges, and balancing those.

Society has become obsessed with sex and sexuality. It worries me how it might affect not only the perceptions of children and young people, but also adults. Intimacy doesn’t have to mean red-blooded lust. The experience of the healthy alternative – a mature and respectful intimacy that is appropriate and safe – is just as valuable. An environment where each can discover their own individuality and how to relate to others, safely and in depth.

The same principles of honesty and respect apply across the full range of intimacy. From the complexity of sex to the simple touch of one hand on another. The safe sharing of deep feelings between friends by whatever means is important for everyone.

By Jonathan

More on Disability Horizons…