After the thoughtful conversations sparked by Joanna Grace’s recent article “Age Appropriate or Person Appropriate?”, we’re delighted to share her latest reflection — one that invites us to think more deeply about how society describes and understands learning disability.

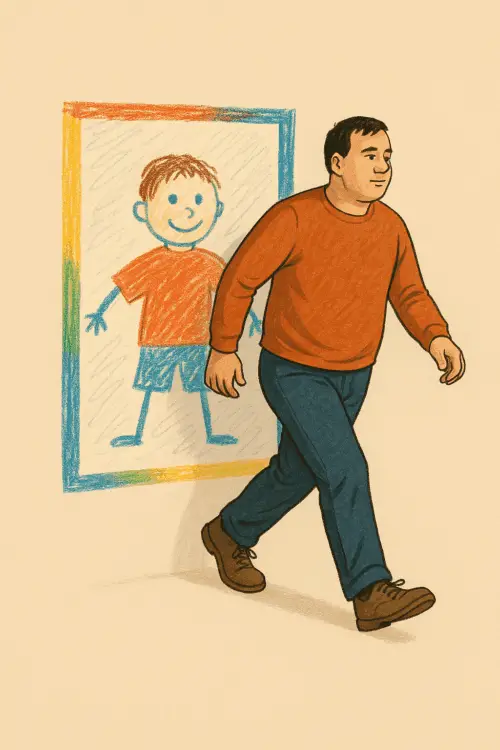

In this new piece, Joanna — founder of The Sensory Projects and a long-standing advocate for people with profound and multiple learning disabilities — explores the language of “mental age” and how everyday comparisons such as “he’s just like a five-year-old” can shape our expectations in ways we may not intend.

Drawing on years of teaching, training, and lived experience, Joanna encourages readers to reflect on what these phrases really mean — and what they might miss. Her writing reminds us that language influences how people are seen and supported, and that true inclusion begins with recognising adults with learning disabilities as adults, with full lives and their own choices.

Key Takeaways

| What you need to know | Simple explanation |

|---|---|

| This blog talks about the words we use | The way we talk about people with learning disabilities matters. |

| “Mental age” is not always a helpful phrase | Saying things like “he’s like a 5-year-old” can oversimplify who someone is. |

| People are not children | Adults with learning disabilities are still adults. |

| They have real lives | They may need support, but they can have jobs, relationships, and make choices. |

| Comparing adults to children can be limiting | It can make it harder for people to be seen and treated as adults with full lives. |

| Support should give people control | Help should let people live their lives, not lives controlled by others. |

| Everyone has the right to make choices | Even choices that aren’t perfect or “healthy.” That’s part of being human. |

| Think before using age comparisons | Ask yourself: what do I really mean? Is it about one skill or the whole person? |

Why this matters

- Words shape how people are treated.

- Adults with learning disabilities should not be spoken to or treated like children.

- Everyone deserves respect, freedom, and the chance to live a full life.

Now, in her own words, Joanna shares her reflections on why comparing a learning disabled adult to a child can never tell the whole story.

Where I First Heard This Language

When my sister and I were at primary school, my mum worked for the Family Fund and the Independent Living Fund. Her job was to visit families applying for grants and to write reports recommending whether they should receive them. Well, it was technically to judge whether to recommend them or not, but I can’t remember her ever refusing anyone!

She wasn’t allowed to tell us the details of the families she met, but over the dinner table she would join in as we all talked about our days:

“I visited a wheelchair user; they wanted a new washing machine.”

“The family had a son with Down’s Syndrome and they wanted a holiday.”

From time to time, I might have heard her say something like, “He was 32 but more like a three year old,” or, “She was 18, but with the mental age of a one year old.”

Thinking About Simple Comparisons

I still hear these age equivalent explanations of people with learning disabilities. They can work well for a brief explanation to a knowing audience, but…

And that’s it, isn’t it? There is always a but.

But they’re not the whole story.

But they’re misleading.

But there’s more to it than a quick age equivalence suggests.

What Age Equivalence Really Means

I wonder if there’s anything about yourself you could express with such an age equivalence. I stopped playing chess against my son when he beat me at six (I know, I should be more mature about it, but it’s no fun as a forty year being beaten by a six year old, and he has plenty of other people to play). So I might say, “I’m a six year old in terms of chess,” or, “When it comes to golf, I’m at the level of a five year old,” which is also true.

But when I say these things you know I mean them in relation to a specific skill, not as an actual equivalence. A five year old could quite rightly point out that the golf clubs are far better suited to my size than theirs. It’s not the same. I’m not the same as a six year old at chess, nor a five year old at golf, and a thirty two year old adult is not equivalent to a three year old, nor an eighteen year old adult to a one year old.

When people use these comparisons they often mean them in relation to a particular skill, usually communication. So, a reasonable response when someone says, “Oh, he’s just like a five year old,” might be to ask, “In what regard?”

The Reality of Adult Experience

Language is powerful, it shapes understanding and creates expectations. I have a friend about whom people sometimes say, “He’s at the level of a five year old.” My friend is twenty three. His communication is roughly what a school might expect from a Year 1 or 2 child: he can read simple sentences, his writing is round and a little bouncy, he’s very chatty. But he is not a five year old. He’s a sexually aware young man with twenty three years of life experience to draw upon in conversation.

My own son is five at the moment. He lives in a brain not hampered by epilepsy; so far as I know, he doesn’t have any issues transferring things to memory; he has a capacity to learn that my friend does not. You would rightly expect very different things of my son and my friend.

Infantilisation and Control

In the past disabled people have been infantilised… who am I kidding? In the past! Speak to any learning disabled person and they’ll tell you about the head tilt and the cutesy tone people adopt when talking to them. As a society, we are comfortable thinking about disabled people as children, happy for them to sing songs, play with toys, make friends. We are far less comfortable seeing them explore adulthood: drinking, smoking, having sex, driving.

Perhaps, as you read “smoking,” you thought (as I did while typing it), “But smoking is bad for you; disabled people shouldn’t be allowed to smoke.” And there, in that word allowed, lies the power imbalance. We think of disabled people as living under someone else’s control.

What would you want for your own life? To be in charge? To be allowed to make mistakes? To make bad choices? (I bet you have some good stories about bad choices you have made) To do unhealthy things? Or would you want someone else enforcing a “good” life on you?

A person with a learning disability may always need some degree of support to access life—but that support should exist so they can live their life, not some pre-approved version of it. Support should enable decision making, with the understanding that they have as much right to make a bad decision as anyone else.

The Different Levels of Impact

At best an age equivalence marks a level of achievement in a specific area, but even then it’s inaccurate, as it’s being drawn between people with different brains, capacities, and potentials. It can create expectations of behaviour and engagement that cannot be met.

At a mid-level age equivalents focus on cognitive capacities and ignore others. Many people with learning disabilities possess an emotional maturity equivalent to their peers. They mature sexually, form relationships, and express creativity—areas often untouched by cognitive difference. By reducing someone to an “age” based solely on cognition, we narrow what it is to be human to intellectual experience alone.

At worst age equivalents infantilise. They feed a collective belief that learning disabled people are simple, one dimensional, childlike creatures to be patronised and pitied—rather than autonomous humans with full, complex lives to be led.

Further Reading and Academic Sources

- Beart, Hardy & Buchan (2005): How People with Intellectual Disabilities View Their Social Identity

This academic review explores how language and social attitudes affect self-image and identity for people with intellectual disabilities.

Read the article - British Institute of Learning Disabilities (BILD): Positive Behavioural Support Competence Framework (2016)

Comprehensive guide detailing best practice PBS for people with learning disabilities, focused on supporting individuals in their own life context rather than using “mental age” comparisons.

Read the official framework - Hollomotz (2011): Learning Difficulties and Sexual Vulnerability

Book summary: Reveals how overprotection and “vulnerability” labels can restrict autonomy for adults with learning difficulties, and how better support and education can improve safety and independence.

Book details - Mencap: Am I Making Myself Clear? Guidelines for Accessible Writing

Essential UK resource with tips for writing respectfully and inclusively about people with learning disabilities; explains why childish or patronising language is harmful.

Read the PDF - UK Department of Health: Valuing People—A New Strategy for Learning Disability (2001)

Landmark UK government policy outlining rights, inclusion, and autonomy for adults with learning disabilities.

Full strategy document