The Way We Were

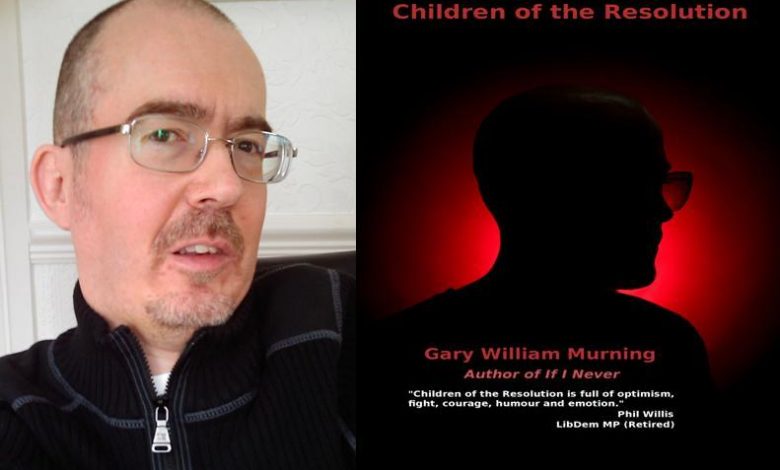

New DH contributor, Gary William Murning, is a novelist living in the northeast of England. His work, largely mainstream fiction, focuses on themes that touch us all — love, death, loss and aspiration — but always with an eye to finding an unusual angle or viewpoint. Gary kindly shares this insightful and thought provoking article about the inspiration behind his new book, Children of the Resolution.

Late in 2007, I started work on my latest in a long line of (at the time unpublished) novels – a piece of work that was originally entitled ‘Children of the Revolution’, after the T-Rex song, and which ultimately became ‘Children of the Resolution’. This novel was intended to be something of a new start. A novel that returned to my earlier attempts at semi-autobiographical fiction and which would, I hoped, successfully communicate some of my own experiences of the introduction of integrated/inclusive education for disabled children in the UK in the mid-1970s.

I had many reasons for wanting to write ‘Children of the Resolution’. It was not intended to be a cathartic affair. The few daemons that had haunted me from that period had by this point been well and truly exorcised. Nevertheless, there were certain points I wanted to make – largely concerning the universal nature of “childhood”, how we all as children undergo very similar experiences, whether disabled or able-bodied, whatever the particular environment in which we find ourselves. My hope – or one of them, at least – was that it might adequately convey the joys and tribulations of the very specific childhood world I’d inhabited in such a way that those who had not been there would see how close these experiences were to their own. I didn’t want to tub thump, to vehemently proclaim ‘We are just like you!’ – I wanted to give readers the space to discover this for themselves – to grow indignant at the quite casual injustices, but also understand that, had circumstances been only slightly different, these experiences could have been their own.

As well as this, however, I knew I was writing a story – one very solidly grounded in factual experience – that needed to be told. The documented history of “disability” is a very patchy one. Given that, from a historical perspective, people with disabilities have often been something of an “underclass”, poorly educated and often impoverished, the opportunity for first person accounts has always been pretty thin on the ground. Today, thankfully, this is changing. With the advent of blogging, greater educational opportunities, technology that allows us to communicate more effectively and immediately, it’s fair to say that future social historians will have much more to work with.

Prior to the 1970s, however, and possibly even into the 1980s and 1990s, so many voices went unheard. Granted, academic study occurred. As I’m sure still happens today, children like me were visited by scholarly types on occasion and asked pertinent questions regarding special school versus mainstream school education – “Do you get bullied?”, for example (a leading assumption that, however serious the issue, I found especially offensive!). On the whole, however, it occurred to me that so many important stories were being lost. I didn’t for one moment believe that this novel could ever claim to speak for all of those unheard children – children like my best friend, Geoff, who had died when he was just seventeen – but I knew I could at least share my own story of those times, reflect some of the casual cruelty with which some of my friends had had to contend (and I use the term “casual cruelty” only after much consideration).

And so I started work on Children of the Resolution. I outlined it more thoroughly than any of the novels I’d written before it, even though writing it would in many respects be an act of remembrance rather than one of invention. I took care not to paint myself – or the character that represented me – as some kind of “hero”, acknowledging my own childhood prejudices and, hopefully, revealing how events contributed to the shaping of the person, the man, I would ultimately become. I’m not sure quite what I’d expected before embarking on this project. Because it was so personal, it’s possible that I’d had certain misgivings, feeling that it would be more taxing and emotionally draining. My blog posts of the period certainly suggest this. However, it was a far easier novel to write than might have been expected. In many regards, it was a joy to revisit those old friends and enemies, to explore the climate of integration – my narrator Carl’s struggle to accommodate the notion of himself as a boy poised between two worlds, for a while not knowing which school he “belonged” to – and the gradual decline once the honeymoon period was over.

Children of the Resolution taught me a lot – not only in the writing but, also, in what came afterwards. Although, at the time of writing this, it has not been my biggest selling novel, the overwhelmingly positive response from readers and, more to the point, their thoughtful comments, enabled me to see that the landscape of “disability” at the end of the twentieth century was a rich one. A socially complex period of actually rather tumultuous change, it revealed in all their glory some very basically human traits: enduring friendship, resentment, love, hatred, the need to conform and the inevitable suspicion that this brought with it, the struggle for equality – opposing forces so often embodied in one conflicting form – fear, grief, hope… the list is pretty endless. It became clear that within the story/stories I had told, there were some quite basic but often unrecognised universal truths laid bare, and in discovering this, something else became very obvious to me; there were more stories to be told – stories that predated my experience and which were quite often more extreme in their essential natures.

And so I found myself returning earlier this year, whilst working on another unrelated novel, to the subject – thinking about social attitudes to “disability” and how all the theories regarding the “social model of disability” et al differed radically to the experience of being a person with a disability. At this time, as now, much was being said in the press regarding benefit changes, about just what “disabled people” wanted, and even when agreeing I felt myself increasingly removed from this strangely mythical concept. As I recently said in a blog post concerning this, “the very idea that I am somehow a member of a minority group is, frankly, something I find quite absurd. Like everyone out there who does not have a disability (although I would argue that we all have a disability, if we define the term broadly enough) I eat, drink, live, breathe, vote, have opinions, voice them, sometimes keep them to myself, watch crap TV, read good books, listen to music, fart, laugh, cry, love, hate and so on. In short, I exist in the same intellectual, physical and emotional world that we all, on the whole, share”. Thinking about this whilst considering the comments of those who had been kind enough to read ‘Children of the Resolution’, I began to understand that if the disparity between how I view myself and how others (as portrayed by the media and, even, charities) view me is still noticeable today, just how considerable would it have been had I been born ten or twenty years earlier? Had my circumstances been rather different – my family life not so grounded in love and quite so supportive – and the world of strangers even less understanding, what other truths might have been discovered within the shadows and the harsh light of those experiences?

I realised fairly quickly, of course, that this was a subject that had to be explored more fully in fictional form. I discussed it with friends and family and, very gradually, started to conceive of a young woman – seventeen years old – awaking politically and sexually in a care home in the late 1940s, a harsh time for the most physically able, with the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust (of which, of course, people with disabilities were among the first victims) still frighteningly fresh.

I began to think about this young woman more and more. Seeing hers as a very closed world, one of private thoughts and, at least initially, unacknowledged ambitions, it became quite clear that for this to work, it would have to be a love story – one in which two worlds would – as they so often do – collide. Forbidden, opposed. Rich with the possibility of eugenics-inspired “but what kind of children will she have” bigotry.

Still in the early research stage of this novel – which now has the title ‘The Wisdom of Closed Worlds’ – surprised daily by just how little historical material there is to work from, I know already it will teach me much. For every perceived hardship I, through my school years, may have witnessed and at times experienced, my female protagonist in ‘The Wisdom of Closed Worlds’ will have tens, if not hundreds to share.

Hers will be a difficult story but, within her struggle, within those recessed parts of her often aching heart, will be found if not enlightenment, then at least a slightly better understanding of the way we were, the way we are – the way we all, whether “disabled” in the conventional sense or not, will always be.

Essentially and unapologetically human.

By Gary William Murning

Children of the Resolution, was published early in 2011. For more information please visit Gary’s Amazon page. Late in 2011, Gary also set up his own micropublishing company, GWM Publications, with the intention of publishing his own work not considered a good fit for his current publisher. The experience of having full creative control, whilst daunting, is something he relishes. The first GWM Publications release is The Realm of the Hungry Ghosts and is available now for pre-order.