Why wheelchair fencing could be the sport for you

This is an updated post from our archives. The article explores the author’s journey of overcoming challenges associated with a congenital neuromotor condition, leading to the discovery of wheelchair fencing as an empowering and inclusive sport. It delves into the physical and psychological benefits of engaging in adaptive sports, highlighting how wheelchair fencing can enhance self-confidence and physical well-being.

Update:

Exploring Adaptive Sports: Wheelchair Fencing and Beyond

Engaging in adaptive sports offers numerous benefits for disabled people, including improved physical health, increased self-esteem, and expanded social connections. Here are some adaptive sports to consider:

- Wheelchair Basketball: A fast-paced team sport that enhances cardiovascular fitness and teamwork skills. Learn more at British Wheelchair Basketball.

- Para Swimming: An excellent way to improve muscle strength and flexibility, suitable for various disability levels. Visit British Swimming for more information.

- Sitting Volleyball: A dynamic game that boosts hand-eye coordination and agility. Find out more at Volleyball England.

- Adaptive Rowing: Builds endurance and upper body strength, with opportunities for both recreational and competitive participation. Check out British Rowing for details.

Participating in these sports can lead to a more active lifestyle and help in building a supportive community. It’s essential to choose an activity that aligns with your interests and physical abilities. According to the English Federation of Disability Sport, participation in regular physical activity can reduce the risk of chronic illnesses by up to 50% and lower the risk of early death by 30%.

Original post follows:

Deputy editor of Disability Horizons, Karen Mogendorff, recently discovered wheelchair fencing. It is a relatively unknown adaptation of a classic combat sport and one of the oldest Paralympic sports. Fencing has been called physical chess and is accessible to people with and without disabilities. Find out whether it’s right for you…

When I tell people that I attend wheelchair fencing classes, they either say ‘cool’ or ‘Do I need to be afraid of you?’ They are also curious – they have never heard of wheelchair fencing.

In this article, I will explain what wheelchair fencing is and what I love about it, as well as share a video from a recreational fencing tournament. I have also included a short review of Into the frame, the only book that I could find that specifically focuses on wheelchair fencing.

Who knows, perhaps wheelchair fencing is something for you…

The Three Musketeers – unlikely role models if you have a walking impairment

Most people are familiar with Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers. The musketeers are the epitome of wit, physical fitness, courage and loyalty to king, country and friends.

As a child, I was particularly enamoured with the novel about the fencer Scaramouche by Rafael Sabatini and the oriental thriller The Ninja by Eric van Lustbader. The combination of graceful movement and body control with the ability to intelligently use strength to defend yourself and loved ones greatly appealed to me.

I, however, never thought that a combat sport was something I could take part in, given that I have a congenital neuromotor condition that impairs my balance and walking ability.

I generally feel like the clumsy elephant in the room. I occasionally trip over my own feet or lose my balance when someone or something accidentally brushes against or bumps into me. Not exactly the picture of physical grace and agility that is associated with fencing.

Lack of physical self-confidence

Added to my difficulties with movement, the environment I grew up in didn’t help build, what I call, physical self-confidence (I do not lack self-confidence in general).

Added to my difficulties with movement, the environment I grew up in didn’t help build, what I call, physical self-confidence (I do not lack self-confidence in general).

During recurring body examinations, doctors muttered uninspiring monologues. Physicians only talked about how my body deviates from able-bodied norms, not what I actually accomplish on a daily basis. And other people’s negative responses to my atypical walking style don’t foster confidence.

Rationally, I know that I do fine. I am even fitter than most able-bodied people due to a decade-long commitment to cardio fitness. But, still, no matter how fit I am, I will always have poor balance and limited walking capacity. And the latter is generally the only thing people see and respond to.

I have tried fitness classes and sports, such as Pilates and Tai Chi, but instructors found it hard to adapt them to my physical impairments. In my experience, you have to know yourself how to adapt a sport, or you need to be lucky to find a coach or teacher who is actually willing and able to adapt it for you.

Betwixt and between able walkers and proficient wheelchair users

I did not consider specific disability sports, such as wheelchair tennis or fencing, as a viable alternative because these are predominantly for wheelchair users.

I rarely use a wheelchair, and becoming a clumsy wheelchair user instead of a clumsy walker did not appeal to me. So, basically, I did not think that I could become a fencer of any kind. It turned out that I was wrong.

You do not have to be a proficient wheelchair user to be a wheelchair fencer

I had known of the local wheelchair fencing club for years. Its name – Scaramouche – had caught my attention when I researched hobbies for disabled people for work. At the time, I discounted it. I had little spare time and I thought that I had to be a proficient wheelchair user.

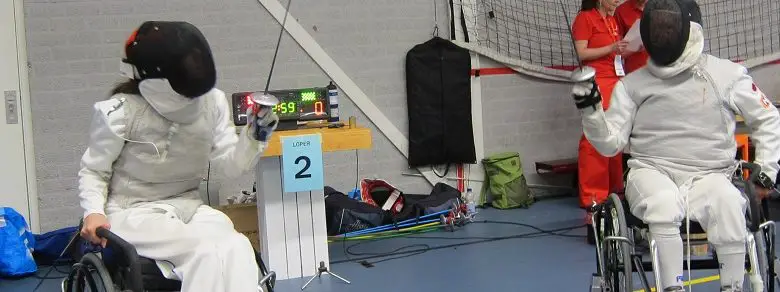

This year, however, I decided to give it a try. To my surprise, you only have to be able to sit in a fixed wheelchair *see image below) and to intelligently wield your weapon to become a fencer. Well, there is a little bit more to it. Fencing isn’t called physical chess for no reason, but I hope you get my point.

The rules of the game – wheelchair fencing with a foil

You can fence with different weapons – a foil, an epee or a sabre. I fence with a foil: a light weapon derived from the court sword.

As stated, wheelchair fencers engage in fencing seated in a fixed sports wheelchair. Fencers wear protective clothing: a jacket, trousers, a mask and a fencing glove on your fencing hand.

A hit is scored when two requirements are met:

1. one has earned the right of way by being:

- the first to attack

- by blocking the attack of one’s opponent

- taking the opponent’s blade

2. the point of the weapon makes contact with the trunk of one’s opponent.

Fencing requires agility, strength and strategic insight. Different strategies may be deployed to earn the upper hand. That is why I like fencing; it is not only about strength, agility and speed but also about strategy. Moreover, a good fight also looks appealing and graceful.

It goes without saying that sportsmanship is as important as scoring hits. After all, fencing is a gentleman’s sport (or gentlewoman). If one behaves unsporty, points may go to your opponent.

Wheelchair fencing tournaments

You can do wheelchair fencing recreationally, or take part in sports tournaments. I don’t have the ambition to participate in it competitively. But I did participate in an informal, recreational wheelchair fencing tournament in June 2019 at the ParaGames in Breda, the Netherlands (where I am from).

The main purpose was to meet other wheelchair fencers. It was fun and very hot – fencing clothes protect you against injury but also make you sweat terribly, particularly in summer. As a beginner, I did not win a medal. But I also did not end up in the last place.

The preliminary rounds of a competition are known as Poule (Pool) rounds. A bout lasts up to three minutes. The victor is the first to score five hits. Winners of the poule rounds go through to the direct elimination rounds.

The knock out rounds last up to nine minutes, divided into periods of three minutes. The winner is the first to score 15 hits.

Review of Wheelchair Fencing book Into the Frame

by Jonathan David Collins and illustrated by Emily Hercock

Into the frame is a self-published book by Jonathan Collins, a British wheelchair fencer with Spina Bifida and poor eyesight. Wheelchair fencing is his passion and he seeks to promote it with his book.

The book is an easy read – basic information about the sport is interspersed with ‘behind the mask’ stories of British and international wheelchair fencers.

The book emphasises how wheelchair fencing has enriched the lives of disabled people with a variety of disabilities from Cerebral Palsy to poor eyesight. It also explains how wheelchair fencing can help you to maintain a healthy weight, to build self-confidence, provide purpose and make new friends.

It also has information on the history of the sport, as well as the clothing, equipment, etiquette and rules. The short personal stories included in the book make it an enjoyable read. I only missed a chapter on techniques and fencing strategies that highlight the chess component of wheelchair fencing.

To find out more about wheelchair fencing, visit the International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation, International Fencing Federation and British Disability Fencing.

By Karen Mogendorff

More on Disability Horizons…

- 5 ways to get fit and stay healthy if you’re disabled

- How cycling helped Nick rediscover who he was after a stroke

- Wheelchair exercise: using Zumba to make fitness more inclusive

Originally posted on 10/08/2019 @ 3:54 pm