Lindsey Dryden: a disabled and queer filmmaker who is making the film industry fully accessible and inclusive for all

Lindsey Dryden makes magic happen as an independent filmmaker from the UK, steering Little By Little Films to fame. She lent her expertise to the Netflix Documentary Talent Fund jury, hunting for talented filmmakers who bring stories from a rich tapestry of backgrounds, cultures, and ethnicities.

Our writer, Emma Purcell, interviewed Lindsey Dryden about her career as a disabled and queer filmmaker, the launch of her production company and her thoughts on disability representation in the film industry.

Lindsey Dryden on being a disabled filmmaker

What is your disability and do you require any support or adaptation when producing films?

Since the age of three, I’ve lived with hearing loss and an accompanying vestibular disorder, a condition that causes dizziness and vertigo.

I’m interested in creating environments with my filmmaking teams where everyone is welcome to bring our bodies into our work so that we can make structures that enable us to thrive.

For some of us, that means scheduling frequent rest breaks or shorter working days, collaborating with a supportive colleague to manage note-taking or spreadsheets, ensuring there’s good light for lipreading, having meetings in quiet environments or ensuring there are facilities for a service animal to rest.

At a deeper level, I find that the best support is working with colleagues who are actively interested in the ways that our bodies shape our experience, who are working on having pride in their bodies in all their complexity (which is an ongoing process for many of us), and committed to an intersectional approach.

I love collaborating with people who share the philosophy of Sins Invalid (a disability justice performance project) – “We know that we are powerful not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them.”

What inspired you to start in British television documentaries and did you face any challenges to secure work in your early career?

I became a filmmaker because I always longed to be involved in storytelling day-to-day. As a kid, I wrote endless adventure stories and recorded weird little talk radio programmes with my sister.

As I got older, I had this quiet but fierce longing to contribute to putting different bodies on-screen and telling the stories I searched for but couldn’t find on TV or film. I initially thought I would pursue a career in wildlife filmmaking because I’d been involved in cetacean conservation and was happiest on a boat with a camera.

But then I realised it was human stories I was most curious about. I found work relatively easily by contacting lots of independent production companies in Brighton (I think it’s much tougher these days).

I was hired as a researcher on a history series, then worked for various other companies, before doing a long-ish stint at Lambent Productions.

I’d say the big challenges in securing work then were finding ethical companies and projects to work on, where I felt comfortable that the programmes weren’t exploitative, as lots of TV was (and still is). Lambent was a great ethical home to work at.

Why did you choose to move into independent filmmaking?

I moved into independent filmmaking partly because I was seeking greater ethical and creative autonomy and partly because I could no longer keep up with the expectations of 60+ hour weeks and gruelling schedules.

By this time I was working in-house for a channel and was having debilitating issues with my vestibular system nearly every day because I was exhausted from overwork (I think this was cumulative, not just linked to that one job).

I didn’t have the language or community back then to know how to ask for accommodations so that I could do my job differently. I just knew that I needed the autonomy to organise my days according to my body’s needs.

So, I took myself out of the TV workforce (as I’ve since discovered other disabled colleagues did too) and I was lucky enough to get some rest for a couple of months by using up my savings. I then started developing independent films that I directed.

Lindsey Dryden on launching her production company Little By Little Films

Can you tell us about how you founded Little By Little Films?

Because I’m a director first, I didn’t set out to run a production company. It evolved organically because I was directing my first feature documentary Lost and Sound (SXSW, 2012) with my brilliant producer Kat Mansoor’s company Animal Monday. I was producing it too so I needed an entity.

So, I formed Little By Little Films and have since had the pleasure of developing the company with a specific ethos and a talented team.

We use a representational model so that the people making editorial decisions are from the communities that are most affected by the storytelling. We focus on brilliant and original LGBTQ+, disabled and women’s voices.

What kind of stories about disability has Little By Little Films created?

We’ve produced feature-length documentary films like Unrest (Netflix/PBS, 2017) – a biographical documentary about a PhD student living with chronic fatigue syndrome.

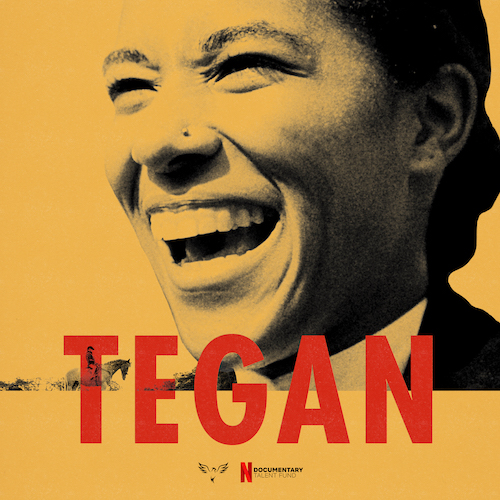

We’ve also contributed as executive producers to short films like the very recently completed Tegan: Dreams of the Paralympics, which is a story about a young black woman with cerebral palsy called Tegan, who is on a mission to compete in equestrian at the 2024 Paralympic Games.

Also, we worked on the 2020 BIFA-nominated The Forgotten C, a short film about a lady called Aisha who is having to shield during the coronavirus pandemic while battling cancer.

You’ve had your films featured in many film festivals and won numerous awards. What has been your proudest achievement so far?

I feel very proud of our film contributors and filmmaking teams across all our productions. It takes such a lot of heart and generosity to be on camera and such creativity and resilience to bring a film to completion.

I’m in awe of many of the folks I get to work with. I think our whole team had a special moment at the Emmy’s when it was announced that we’d won for Trans In America: Texas Strong (2019, ACLU/CondeNast), as it was a win for all the courageous trans people in that documentary series.

Can people watch any of your films online or on streaming services?

Yes – our Little By Little website contains all the viewing links. You can also watch the Netflix Documentary Talent Fund Film, Tegan: Dreams of the Paralympics on YouTube.

You’re also founding members of Queer Producer Collective and FWD-Doc. Can you tell us about these organisations and what your roles are?

Queer Producers and FWD-Doc are two of the communities I feel most grateful for as a filmmaker, with its creative solidarity and collective advocacy being invaluable and energising.

Queer Producers Network (QPN) was founded by Jess Devaney at Multitude Films as a peer-to-peer network of LGBTQ+ identified producers working across fiction and non-fiction. I was one of the founding members back in the early days. More recently, a new organisation called QueerDoc was created to serve the wider queer documentary filmmaking community, which has extraordinary members.

FWD-Doc (pronounced ‘forward doc’) is an advocacy organisation that I co-founded with fellow disabled filmmakers Jim LeBrecht and Day Al-Mohamed and ally Alysa Nahmais, to collectively focus on increasing the visibility of, support for, and direct access to opportunities, networks, and employment for D/deaf and disabled filmmakers.

We were inspired by organisations like Brown Girls Doc Mafia, A-Doc and Firelight. At FWD-Doc, we have 500+ members in several countries. We do day-to-day work with industry bodies and our members to advocate for greater inclusion, accessibility and representation.

I particularly love leading on special projects, like the ‘Toolkit for Inclusion & Accessibility: Changing the Narrative of Disability in Documentary Film’ that we made in association with Doc Society supported by Netflix.

Lindsey Dryden on working with the Netflix Documentary Talent Fund

Can you tell us about the Netflix Documentary Talent Fund and how you’ve been involved?

The Documentary Talent Fund was launched by Netflix and WDW Entertainment in December 2020 and was open to anyone across the UK to pitch their documentary idea for a potential commission.

The Fund’s goal was to encourage new opportunities for emerging filmmakers and to nurture brilliant and under-represented new filmmaking talent in Britain. I was invited to be a juror on the Netflix Documentary Talent Fund when the shortlist had been whittled down to 21 filmmaking teams.

in May 2021, we listened to 21 great pitches and then 10 final films were selected by Netflix and the jury. Then I was invited to act as a mentor/executive producer with one of the selected film teams – the wonderful Ngaio Anyia and Aodh Breathnach, who made Tegan.

You can also check out the winning recipients from the 2022 Documentary Talent Fund, which took place last month.

What kind of content did people submit, who was eligible and how did they apply?

Netflix received thousands of submissions from a diverse range of filmmakers, aged 18 and over. The application process involved entrants submitting a logline, a brief synopsis and a creative statement about their documentary short idea.

Longlisted films were asked to share supporting materials to strengthen their application, including a video pitch. The documentary’s short ideas were chosen for their creativity and vision, and for fulfilling the brief to tell brilliant British stories.

The ten final films encompass a variety of ideas and together they shine a light on a variety of perspectives on British life, culture, and experiences. They explore topics of identity, community, self-belief, empowerment, disability, gender diversity, politics, love, legacy, and many more.

Collectively, the films highlight the talent and stories of people who’ve been marginalised and excluded in British creativity and social life – and they’re full of heart, humour and fun.

Lindsey Dryden’s thoughts on disability representation in the film industry

Do you think enough has been done to represent disability in the film industry and if not, what more needs to be done?

Legendary disability rights activist Judy Heumann said: “Disabled people in film, on television and in other forms of media should reflect the reality of our lives. Our joys, sorrows, struggles, victories and the everyday issues we all face. Only then will we be able to effectively counteract the themes of our being invisible or seen only as incapable, a drain or a tragedy”.

I absolutely subscribe to that belief – and we’re still only 1% of characters on-screen, even fewer of us working in editorial decision-making roles in film and TV. So, the industry has a lot of work to do.

Part of what we can easily do, whether we’re starting out or established, is to think, “Who’s at the table here? Does my thinking, my casting and my crewing up include all of the perspectives that exist in society? Women, people of colour, Deaf and disabled people, LGBTQ+ people, economically vulnerable people, for example?”

New and established filmmakers can take steps to welcome a genuine range of collaborators to their projects and infrastructures, now more than ever. It’s so easy to find new colleagues through Twitter, Instagram or in groups like Queer Producers, FWD-Doc and Brown Girls Doc Mafia.

It’s actually really straightforward to meet talented people in film with different perspectives, or from different communities. What it takes is being prepared to genuinely listen and reshape your practices or expectations. We can all be proactive about expanding who gets the opportunity to contribute to storytelling.

What advice would you give to other disabled people wanting to become filmmakers?

I think the most important thing is to cultivate a deep belief that your stories are valuable and that your bodies are valuable too. Find your community and your filmmaking people through membership organisations like FWD-Doc and Deaf & Disabled People On TV (DDPTV), training courses, social media, film festivals (where you can access them – that’s a whole extra conversation!), talks, masterclasses etc.

Seek out authentic and ethical disabled-led companies and organisations where your value as a disabled person is understood and you can focus on creativity and collaboration instead of advocacy. I think we’d all much prefer to be doing the actual creative work, rather than convincing the wider industry that we’re worth their time.

Immerse yourself in the Social Model of Disability and the work of Sins Invalid and Disability Justice. Discuss all these topics with your filmmaking community, and support each other’s vision.

Work intersectionally and bring others with you. Find ways to do paid work to sustain yourself (it doesn’t even have to be film work) while also developing your independent voice and projects and actively developing relationships with companies and people you admire in the industry.

Be in solidarity with each other to require sustainable and accessible work environments. The wider film industry is gradually recognising that we are one billion people in the world and we’re a huge and underserved audience.

Collaborate with fellow talented and ethical people to bring your brilliant stories to the audience that’s long been waiting for them – it’s time.

Find out more about Lindsey Dryden by following her on Twitter and Instagram.

Interview by Emma Purcell

More on Disability Horizons…

- Turning my passion for films into a career as a disabled film editor

- Crip Camp: a documentary that celebrates the disability revolution

- 10 influential disabled LGBTQ+ activists to follow

- Check out our NEW disability awareness cards on the Disability Horizons Shop

Originally posted on 12/03/2022 @ 11:00 am