Beyond the Scale: How Supportive Health Habits Can Boost Mental Wellbeing and Everyday Mobility

Many disabled people and those living with long-term conditions want better energy, steadier mood, and more comfort in their bodies — but face barriers that have nothing to do with motivation. This article explores how movement, nutrition, and inclusive non-surgical options can support confidence and mobility, while recognising the structural barriers that shape health choices.

Key Takeaways

| Topic | What to Know |

|---|---|

| Physical and mental health | Gentle, adaptive movement improves mood and stability, even in short sessions. |

| Barriers | Inaccessible gyms, cost, and poor clinical advice limit choice — not lack of effort. |

| Nutrition | Steady, realistic eating habits support energy and clearer thinking. |

| Non-surgical options | ESG, lifestyle programmes, and RF/ultrasound treatments can help some people, but aren’t suitable or necessary for everyone. |

| Social Model framing | Health choices should respect autonomy, comfort, and lived reality. |

| Practical tools | Includes a “tiny steps” weekly plan and questions to ask clinics. |

A realistic look at health and mobility for disabled people

For many disabled people, staying active or improving fitness isn’t a simple case of joining a gym or following generic advice. Lack of transport, poor access, inflexible trainers, and assumptions about ability shape what’s possible — long before anyone thinks about motivation.

“It’s not easy for me to even get to a gym, many are up stairs with no lifts and don’t have accessible equipment”

These barriers are part of the environment, not personal shortcomings. The Social Model of Disability makes that clear, and it’s a grounding point for any conversation about health.

Still, many disabled people want steadier mood, a bit more confidence, and the kind of strength that makes everyday life feel easier. Supportive habits — adapted to real-world limitations — can play a meaningful role.

How mental wellbeing shifts when the body feels supported

When you live with chronic pain, fatigue, or mobility loss, your body can feel like it sets the pace of your life. That has a direct effect on mood.

Research published in JAMA Psychiatry in 2022 found that regular movement can significantly lower a person’s likelihood of experiencing depression, and even short sessions of adaptive exercise can boost energy and help with focus.

These activities help release endorphins — natural mood-boosting chemicals — and reduce stress hormones in the body.

What movement looks like varies widely. For someone with chronic pain, it may be slow, supported stretches that avoid flare triggers. A manual wheelchair user might focus on shoulder mobility to reduce strain during transfers and pushing. People with balance-related conditions can benefit from seated core exercises or supported standing frames. Someone with fatigue conditions might only manage 2–3 minutes at a time, with long rests, which is still helpful. Don’t think that you need to do intensive exercise — it’s all about comfort, confidence, and maintaining the range of motion needed for daily life.

Consider:

- supported standing or gentle stretches

- chair-based strength work

- physiotherapy

- short walks with rests

- light resistance exercises using everyday objects

None of this needs specialised equipment or a gym. Each option can help settle emotions, improve rest at night, and build a steadier sense of confidence.

Tiffiny Carlson, a C5/C6 quadriplegic, talks openly about what regular stretching does for her. She explains that when her body doesn’t move for long periods, her joints and muscles tighten in ways that can cause serious problems. With consistent stretching, she avoids that stiffness. She also says that certain stretches give her a noticeable lift in energy and help her feel more present in her body.

Simple habits like this demonstrate how adaptive movement can support mood and stability without demanding equipment or major time commitments.

Getting out of the house

Short trips outside make everyone feel better. A manual wheelchair user often works their core, shoulders, and arms even during a quick trip to the end of the street. Someone using a power chair might notice the benefit of shifting posture, seeing new things and a change of perspective. Even a tiny route you can manage comfortably works, especially if you know where the rest points are.

There is value in getting out no matter how small the distance you travel. It comes from a change of light, surroundings, and pace. Taking in a different view and letting the movement improve your internal balance and energy. Small bits of activity, in whatever form works, can help the body feel looser and keep spirits up across the day.

Changing Eating Habits

Nutrition plays a different role when you live with pain, fatigue, or a condition that affects appetite. Many disabled people describe days when cooking isn’t realistic or when medication changes hunger cues. Small, predictable habits can still help.

Eating at roughly the same times each day, keeping easy-to-open snacks nearby, or using tools like a lap tray or adapted grips can make meals less draining. Staying hydrated also helps with brain fog, muscle tension, and medication side effects — issues disabled people often juggle daily. These aren’t dramatic changes; they’re small adjustments that support steadier energy.

What changes first: confidence, comfort, and clarity

For many disabled people, the first changes aren’t visible ones. They show up in everyday tasks — maybe transferring feels smoother, or there’s a bit more predictability in energy, and movements that usually trigger discomfort feel less sharp. People with fatigue-related conditions sometimes find their concentration improves after adding short bouts of gentle movement.

To summarise:

- Energy feels more predictable.

- Mood steadies.

- Tasks feel less draining.

- Social plans feel less overwhelming.

Inclusive, non-surgical options that some people find helpful

Weight loss and disability is a deeply under-discussed topic, yet it highlights the importance of finding safe, inclusive, and adaptive support systems that respect each person’s physical and emotional realities.

Some readers may look for additional medical or structured support, especially if long-term mobility loss, medication changes, or hormonal conditions have affected weight, appetite, or comfort.

Non-surgical options can have a useful place in someone’s health journey. Effective non surgical weight loss services like those from Bariendo bring together emotional support, therapy, and practical routines that focus on day-to-day habits. The aim isn’t a dramatic overhaul, but a steadier relationship with your body and a way to rebuild trust in yourself.

The aim here isn’t to “fix” a body. It’s to offer information so people can decide what feels right for them.

Below are examples of non-surgical approaches people sometimes explore. These are not recommendations — they are options to research, question, and assess with professionals who understand disability.

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty (ESG)

ESG reduces stomach volume internally using an endoscope. It avoids external incisions and usually has a short recovery period.

Why some people choose it:

- Long-term mobility changes have affected metabolic health.

- Previous attempts to manage weight have been limited by pain or fatigue.

What to ask a provider:

- How do you adapt pre- and post-procedure plans for disabled people?

- Can a carer be present during appointments?

- What access features does the clinic have (doors, lights, seating, parking)?

- How do you handle complications for people with reduced mobility or fatigue?

Accessibility note: ESG is typically private-clinic only and can be expensive. Balanced information is also available through NHS bariatric services, which offer clear guidance on risks and benefits.

Lifestyle and behavioural programmes

These services combine nutrition guidance, physiotherapy-informed movement, and emotional support.

Why they may help:

- They focus on small, repeatable habits rather than restrictive rules.

- Sessions can often be adapted for wheelchair users or people with chronic pain.

Research on online mental health peer support forums shows that “safe and active forums that provide convenient access to information and advice can lead to improvements in mental health self-efficacy.” This highlights how social and emotional support complements physical habits for better mental wellbeing.

Key questions to ask:

- What training do staff have in disability inclusion?

- Can sessions be done remotely?

- How are rest breaks handled?

Radiofrequency or ultrasound-based treatments

Some people use these options to improve comfort, skin firmness, or specific fat areas linked to medication or hormonal shifts.

What to know:

- They are non-invasive and usually pain-free.

- Results vary widely.

- Not suitable for everyone; careful screening is essential.

Questions to ask:

- How do you adapt positioning for wheelchair users or people who cannot lie flat?

- What side effects should I expect based on my condition?

Mind–body integration

Many clinics now include counselling, mindfulness, or peer support alongside physical treatments.

Why it matters: Disabled people often report that stress, uncertainty, and past medical trauma affect eating patterns and how safe they feel in health settings. Emotional support can reduce that load. A study on peer support forums found that these spaces offer convenient access to information and advice that can improve mental health self-efficacy — showing that emotional support matters as much as physical intervention.

A short “tiny steps” plan for readers with fatigue or pain

This is a practical tool readers can use without equipment:

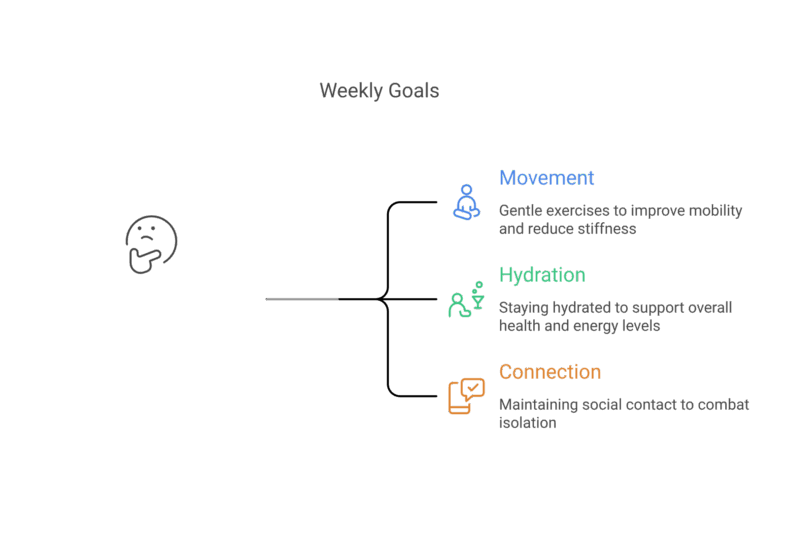

Three small actions for the week

These steps are deliberately designed for readers who experience variable pain, fatigue, or limited mobility. The goal is predictability, not intensity:

Movement: 3–5 minutes of gentle movement that suits your body — this could be seated stretches, shoulder mobility work for wheelchair users, or slow leg raises for people who spend long periods in bed or in a static position.

Food: A glass of water with each meal, or keeping a bottle within reach for people who can’t stand and refill frequently.

Connection: A check-in message, voice note, or phone call — especially useful for readers who experience isolation due to transport barriers or fluctuating health.

These tiny actions fit around energy limits, care schedules, and unpredictable symptoms.

If you explore a clinic, here’s a short checklist

When exploring any clinic, disabled readers might consider:

- Whether the entrance, treatment rooms, and toilets are fully accessible — not just “step-free,” but spacious enough for turning, transferring, and equipment.

- If staff understand conditions that affect fatigue, pain, sensory processing, or muscle tone.

- Whether adjustments can be made for people who can’t lie flat, sit for long periods, or tolerate bright lights or noise.

- If appointment times can be extended or spaced out to avoid overexertion.

- Whether aftercare is designed for people who use mobility aids, have limited grip strength, or rely on carers.

This ensures decisions are shaped by access, not pressure.

Building health on your own terms

Better health is a marathon not a sprint! Building gradually, it comes from noticing what helps you feel more settled and at ease in your body, and doing that in ways that work with the access barriers you face rather than forcing yourself through them.

For many disabled people, the greatest relief comes from realising they don’t have to chase someone else’s idea of “healthy.” They can build habits that match their own capacity, values, and environment. Health support should meet people where they are, not require them to squeeze into inaccessible systems.

Every small improvement — steadier energy, clearer thinking, a more comfortable step or transfer — is worth acknowledging. None of it needs perfection. It simply needs options that respect lived experience and choice.

Disclaimer: This article is for general information only and is not a substitute for personalised medical advice.