How Much Collagen Per Day to Support Joint Health

Can Collagen help disabled people?

How Much Collagen Per Day Might Help With Joint Pain – and When It’s Worth Considering

Joint pain, stiffness, and reduced movement are part of daily life for many disabled people. This can include people with arthritis, chronic pain conditions, hypermobility, connective tissue disorders, long-term injuries, or impairments that place extra strain on certain joints.

Collagen supplements are often suggested as a way to “support joint health”, but the advice online is usually aimed at athletes or gym-goers, not people living with disability. This piece looks at what collagen does, how much is commonly used, and when it may – or may not – be worth trying, without assuming everyone has the same body, budget, or access needs.

Key takeaways: collagen and joint pain for disabled people

| Key point | What this means in practice |

|---|---|

| Collagen is optional, not essential | Some disabled people find collagen mildly helpful for joint comfort. Many notice no change at all, and that is normal. |

| Any benefit is usually small | Research shows modest changes in pain or stiffness for some people, not dramatic improvements. |

| It works slowly, if it works at all | Changes, when they happen, often take 6–12 weeks. Quick results are unlikely. |

| Collagen is not a treatment or cure | It does not repair joint damage, reverse arthritis, or remove access barriers. |

| Typical doses fall within a range | Studies often look at 5–15 grams per day, rather than one fixed amount. |

| More is not always better | Higher doses cost more and are not guaranteed to help more. |

| Results vary from person to person | Bodies, impairments, access needs, and daily strain on joints all differ. |

| It should not replace support or adjustments | Supplements are never a substitute for mobility aids, pacing, pain management, or access changes. |

What collagen actually does in the body

Collagen is a protein found naturally in cartilage, tendons, ligaments, and other connective tissue. In joints, it helps cartilage cope with pressure and movement.

As we age or experience repeated strain, the body’s natural collagen levels decline. This can contribute to joint stiffness, slower recovery after movement, reduced cartilage resilience, and increased wear over time.

Some disabled people experience:

- joint pain linked to long-term conditions

- faster wear in certain joints due to mobility aids or uneven load

- slower recovery after movement

- connective tissue weakness or instability

In these situations, collagen is sometimes suggested as a supportive option, not a treatment or cure.

It’s important to be clear: collagen supplements do not reverse joint damage or remove the barriers disabled people face. Any benefit is usually modest and gradual.

If collagen is digested like any other protein, how can it affect joints?

A common and reasonable question is whether collagen supplements can really do anything specific for joints, or whether they are simply broken down into amino acids like any other protein you eat.

The short answer is: most of it is digested like protein, but not all of it behaves the same way.

When collagen supplements are digested, they are broken down into:

- free amino acids, and

- very small collagen-specific peptides, particularly ones rich in proline and hydroxyproline.

Blood studies show that after taking collagen, some of these small peptides enter the bloodstream intact for a short time, rather than being fully broken down into single amino acids. This matters because these peptides appear to be recognised by cartilage and connective tissue cells in a different way from generic dietary protein.

What those peptides seem to do

Laboratory and animal studies suggest these collagen-derived peptides can interact with joint tissue cells rather than acting only as fuel. In particular, they appear to:

- encourage cartilage cells to maintain the tissue that cushions joints

- slightly increase production of cartilage matrix components

- reduce some of the breakdown processes linked with osteoarthritis

This is sometimes described as mild chondroprotection. It does not rebuild damaged joints or stop arthritis progressing, but it may help slow wear in some people.

What human studies show

In people, the effects are small but consistent enough to be measurable in some trials.

Studies of collagen peptides taken daily for several months, most often in knee osteoarthritis, show:

- modest reductions in pain compared with placebo

- small improvements in stiffness and function

- good safety over medium-term use

Researchers are careful to point out that results vary between individuals and products, and that collagen should be seen as a low-risk add-on, not a core treatment or replacement for pain management, physiotherapy, or access to appropriate support.

A clean, transparent option like this collagen peptides protein provides hydrolyzed collagen peptides with no unnecessary ingredients, making it easy to use every day in any drink or recipe.

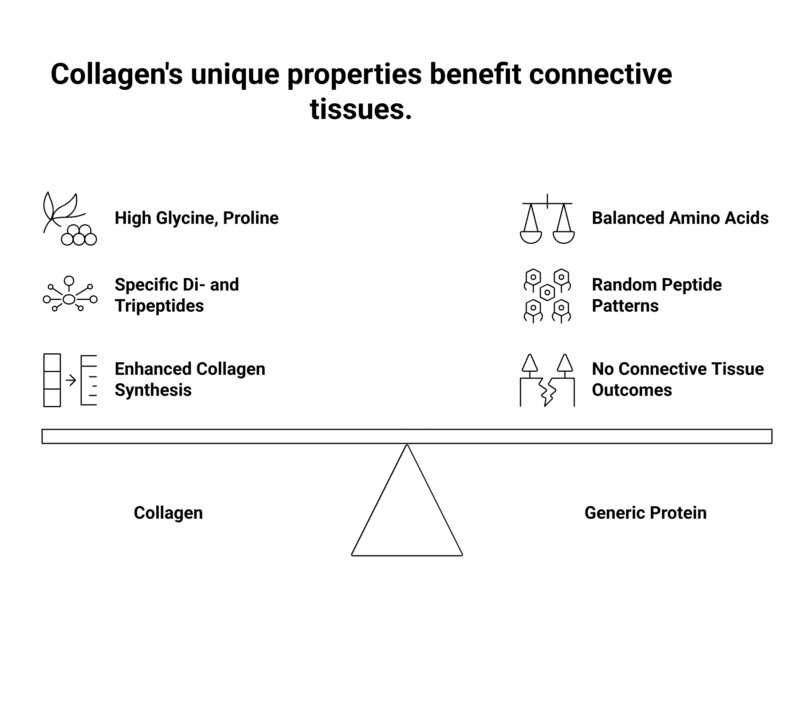

Why collagen isn’t the same as “just more protein”

From a nutrition point of view, scepticism is justified. For muscle strength or general protein intake, food protein or whey is usually more effective and cheaper.

Collagen is different mainly because:

- its amino acids are heavily weighted towards those used in connective tissue

- digestion reliably produces specific small peptides that survive long enough to act as signals

- trials looking specifically at joints and tendons show different outcomes from equal amounts of standard protein

This likely explains why some people report joint-related benefits even though collagen is not a complete protein.

A realistic bottom line

Collagen supplements are not essential, and they do not work for everyone. If they help, the effect is usually gradual and limited. The evidence supports seeing collagen as something some disabled people may choose to try carefully, rather than something anyone needs to take for their joints.

Further reading (authoritative sources)

- Arthritis Foundation – Collagen

Clear, cautious overview from a US arthritis charity, including limitations of the evidence - PubMed Central – Collagen supplementation for joint health

Peer-reviewed review of mechanisms and clinical findings

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10058045/ - Frontiers in Nutrition – Absorption of collagen-derived peptides

Explains what happens to collagen after digestion and why peptides may matter

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1416643/full

How much collagen do people typically take?

There is no single “correct” dose, and research does not agree on one universal amount. Most studies look at ranges, not exact prescriptions.

Commonly studied amounts

5 grams per day

Often described as a minimum amount. Some people report mild improvements, particularly when taken consistently. Some research suggests taking collagen with vitamin C may support its effectiveness, though this isn’t essential.

10–15 grams per day

This is the range most often used in research on joint comfort and stiffness. Some people notice small changes in day-to-day movement after several weeks.

15–20 grams per day

Sometimes suggested for people whose joints are under repeated strain. This is not automatically “better” and may be unnecessary for many people.

More is not always helpful, and higher doses cost more, which matters.

How long might it take to notice anything?

Collagen works slowly, if it works at all for you.

- Some people notice changes after 6–8 weeks

- More substantial effects, when they happen, may take 12 weeks or longer

- Others notice no difference, even after several months

- Improvements, when they happen, tend to be subtle, not dramatic

If there is no noticeable change after around three months, it may not be worth continuing.

What to look for if you decide to try collagen

If you do try collagen, look for “hydrolyzed” or “collagen peptides” on the label – these are broken down into smaller pieces for better absorption.

It’s also worth checking that the product:

- is free from fillers or unnecessary additives

- dissolves easily in hot or cold liquids

- comes from a supplier you trust

Most collagen supplements come from bovine (cow) or marine (fish) sources, so they are not suitable for people who avoid animal products.

How to take it

There is no strong evidence that timing makes a major difference. People usually take collagen:

- mixed into a hot or cold drink (coffee, tea, smoothies)

- stirred into food like oatmeal, yogurt, or soup

- with food to avoid stomach discomfort

- once per day, rather than splitting doses

Collagen powder usually dissolves in hot or cold drinks, including coffee, tea, or smoothies.

Consistency matters more than the time of day.

Safety and tolerability

Collagen peptides are generally well tolerated for long-term use. They are free from common allergens and gentle on digestion for most people.

The most common mistake is under-dosing – taking too little to experience any meaningful benefit.

When collagen might be worth considering

Collagen may be something to think about if:

- joint pain affects daily tasks or comfort

- you’ve already tried other low-cost approaches

- you want to experiment carefully and affordably

It is not essential, and many disabled people manage joint pain without supplements.

When collagen may not be appropriate

Collagen is not suitable or useful for everyone. It may not be a good idea if:

- money is tight and supplements would add pressure

- you already get enough protein through food

- joint pain is driven mainly by inflammation, nerve pain, or structural issues

- you’ve tried it before with no benefit

Some people also prefer to avoid animal-derived products, as most collagen supplements come from bovine or marine sources.

Other ways people support joint comfort

Collagen is only one small piece of a much bigger picture. Depending on the person, joint comfort may also be supported by:

- pacing and energy management

- appropriate mobility aids

- physiotherapy or gentle movement

- pain management strategies

- addressing access barriers that force joints to work harder

Supplements should never be framed as a replacement for support, access, or adjustments.

A realistic takeaway

Collagen is optional, not essential. Some disabled people find it mildly helpful, others notice no difference at all.

If you decide to try it:

- start with a lower dose

- give it time

- stop if it isn’t helping

Your body, circumstances, and access needs are specific to you, and no supplement can override that reality.